In discussions of covenant theology and baptism, there are some paedobaptists who ground the practice of infant baptism on an overall consideration of the unity of redemptive history. It is an argument from analogy. “As it was then, so it is now.” We are told that generic paradigms such as God’s dealings with Abraham, or an oikos principle (it goes by various names), establish the specific practice of baptism in the church. This kind of argumentation grounds covenant administration on an analogy.

The argument from analogy may seem persuasive because it appeals to a true unity in redemptive history, but the argument itself fails careful examination and its methodology opens a door for unlimited arguments of the same nature (such as paedocommunion).

To prove this (and not merely assert it), I offer several pages from a book written in 1654 by John Tombes, a well-known Anglican clergyman who came to antipaedobaptist convictions. Tombes interacted a great deal with the divines of his day. In the text below, Tombes is mostly responding to Stephen Marshall and Richard Baxter. The basic arguments go like this: Tombes’ argues:

If all of the ceremonial laws are abrogated, then a ceremonial law such as circumcision cannot bind the church.

But all of the ceremonial laws are abrogated,

Therefore circumcision does not bind the church.

Stephen Marshall answers:

Where there is an analogy between ordinances, there is an obligation of practice.

But there is an analogy between the practice of circumcision and that of baptism.

Therefore the practice of circumcision binds the church.

Tombes answers:

The institution of a positive law, not analogy, dictates how it is to be observed.

Arguments that ground the observation of positive laws on analogy have no clear boundaries or guidelines, as evidenced by paedobaptists’ diversity of thought on paedobaptism itself.

Tombes asserts that paedobaptists forget their own principles when they make these arguments based on analogy. The antipaedobaptist view of positive law is not at all unique to Baptists or antipaedobaptists. It is an application of Protestant Reformed theology itself to the issue of baptism.

Tombes also pushes back at Marshall’s attempt to make circumcision a part of the substance of the covenant, noting that this is supposed, not proved, and it is contradicted in other ways in Marshall’s arguments.

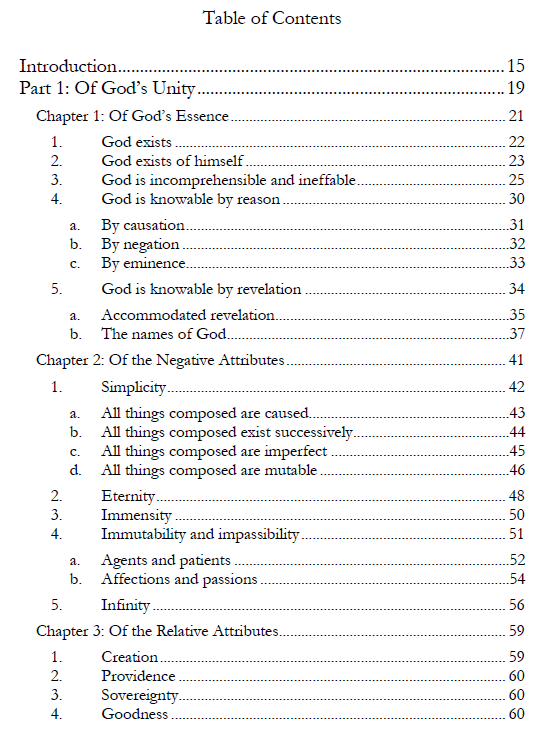

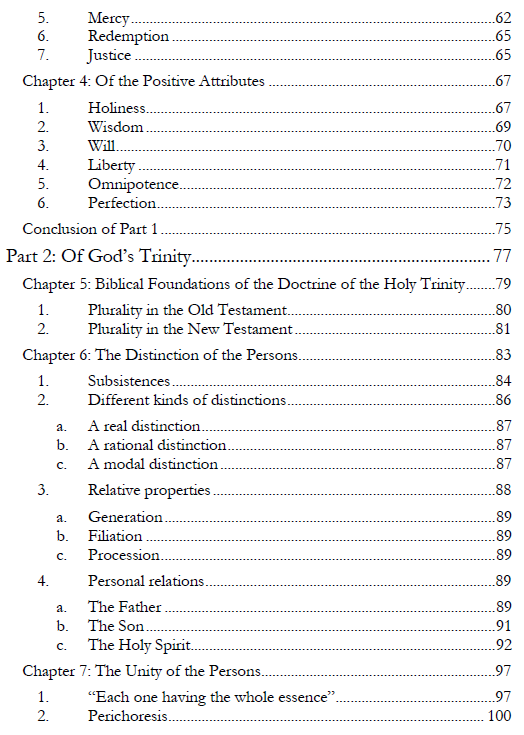

What follows below, in updated spelling, is John Tombes, Anti-pædobaptism, or, The second part of the full review of the dispute concerning infant-baptism in which the invalidity of arguments is shewed, 11-16. Most of the elements in italics are either proper names or quotations which Tombes is including from other authors (mostly Stephen Marshall).

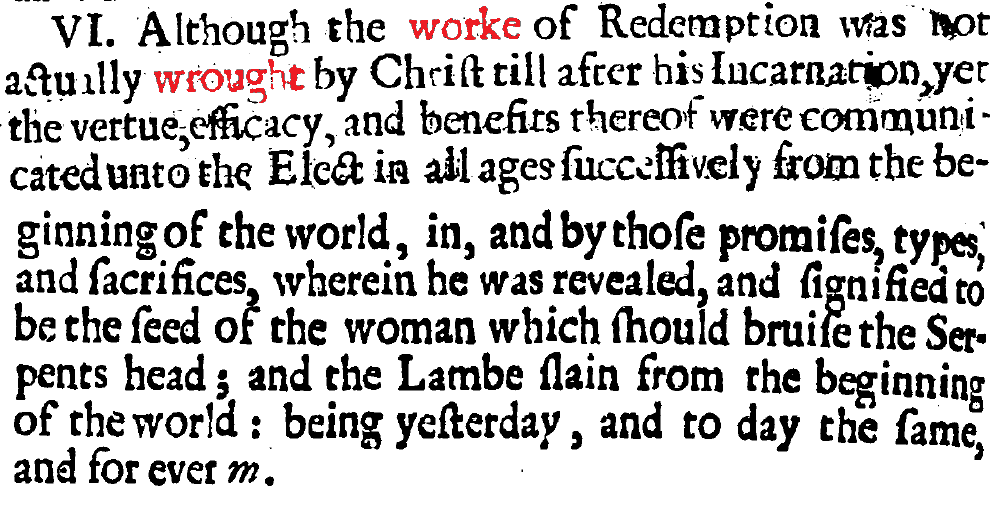

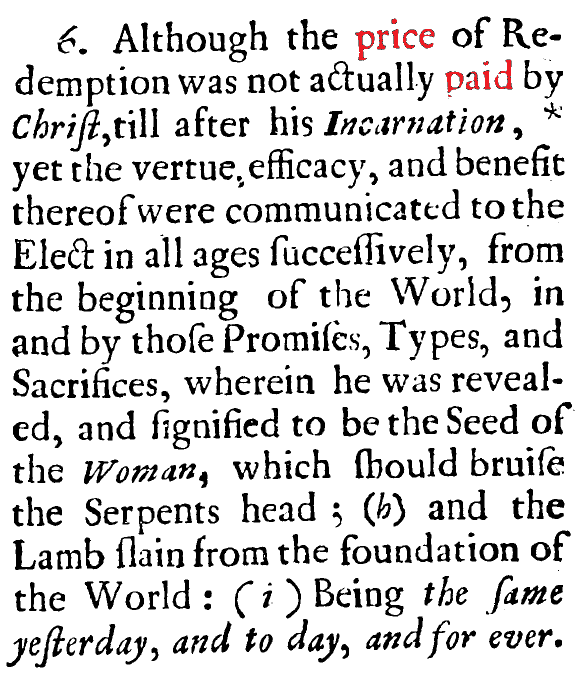

The Assembly at Westminster in their Confession of faith, chap. 25. Art. 4. alleges but one text out of the old Testament, viz. Gen. 17. 7. 9. for admission of Infants by Baptism into the visible Church. And if Mr. Marshall their Champion in this Point express their minds, they deduce Infant-baptism from this principle, All God’s Commands and Institutions about the Sacraments of the Jews bind us as much as they did them in all things which belong to the substance of the Covenant, and were not accidental to them. Which how false it is, how contrary to the Tenet of Divines former and later, is shewed in my Examen, part 3. Sect. 12. to which I may add the Assemblies confession of faith, chap. 19. Art. 3. All which ceremonial laws are now abrogated under the New Testament. And if all of them be abrogated, how can it be true that the law about circumcising Infants still binds? But Mr. Marshall in his Defence pag. 195. conceives his argument good from the analogy of the Ceremonial law of Circumcision, which he calls his Analogical argument, pag. 201.

On the contrary I deny any argument from analogy of the Ceremonial law good in mere positive ceremonies to prove thus it was in the old Testament, therefore it must be so in the new. And thus I argue,

1. Arguments from Analogy in mere positive Rites of the old Testament to make rules for observing mere positive Ceremonies of the new without institution gathered by precept or apostolical example or other declaration in the new Testament, do suppose that without Institution there may be par ratio, a like reason of the use of the one Ceremony as the other. But this is not true; For in positive Rites there is no reason for the use of this and not another thing in this manner to this end, by, or to persons, but the will of the appointer. For there is not anything natural or moral in them; they have no general equity; they are supposed to be merely not mixtly positive. Therefore, where there is not the like Institution, there is not a like reason. And therefore, this opinion of Analogy in positive Rites from a parity of reason without Institution in the new Testament is a mere fancy, and no good ground for an argument.

To apply it to the case in hand, Circumcision and Baptism are merely positive ordinances; Mr. Baxter calls them, p. 9. Positives about worship. Generally, Sacraments by Divines are reckoned among mere positives; Chamier. Panstr. Cath. Tom. 4. l. 2. c. 12. Sect. 20. nulla vera ratio Sacramentorum potest consistere absque institutione. l. 7. c. 10. Sect. 1. nullum Sacramentum est à natura sua, itaque prorsus ab institutione. The places are innumerable in Protestant writers and others to prove this; were it not that I find my Antagonists often forget what is elsewhere yielded by them, I should not say so much, the thing being so plain, that there is nothing natural or moral in them, because till they were appointed (which was thousands of years after the creation) they were not used, nor taken for signs of that which they signified. The reason, then, of Baptism and Circumcision is merely Institution; if then there be not the like Institution, there is not the like reason.

This argument is confirmed by Mr. Marshall’s grant, Defence, pag. 92. 182. the formal reason of the Jews being circumcised was the Command of God. Therefore there is not the like reason of Infant-baptism as of Infant-circumcision without the like command of God. But there is no express command for Infant-baptism as Mr. Marshall confesses, therefore there is not par ratio, like reason of the one as the other.

2. I thus argue,

If all the Laws and Commands about the Sacraments, positive Rites and Ceremonies of the Jews, be now abrogated, then no argument upon supposed analogy or parity of reason from the institution of those abrogated Rites can prove a binding rule to us about a mere positive Rite of the new Testament.

For how can that make a binding rule to us about another mere positive Rite without any other Institution, which itself is abrogated? That which binds not at all, binds not about another thing, v. g. Baptism.

But all the Laws and Commands about the Sacraments, positive Rites and Ceremonies of the Jews, are now abrogated, as is proved in my Examen, part. 3. sect. 12. and confessed by the Assembly Conf. of faith, chap. 19. art. 3.

Ergo none of them bind.

This argument is confirmed by the words of Mr. Cawdrey Sabbat. Rediv. part. 2. chap. 7. sect. 7. pag. 263. No ceremonial commandment can infer a moral commandment. The reason of our assertion is this, because partial commandments given to some Nation or persons (as the Ceremonial precepts were) cannot infer a general to oblige others, even all the world. Again, Sect. 10. pag. 276. First it is so in all other like special and ceremonial Commandments concerning days, whensoever the particular day was abrogated, the whole Commandment concerning that day was utterly abolished, the Law of Circumcision and of the Passover is expired as well as the sacramental and ceremonial actions commanded by that law.

This [issue] Mr. Marshall conceived he had prevented by supposing that in some commands about the Sacraments of the Jews, are some things that belong to the substance of the Covenant, and limiting his assertion to those. And when in my Examen pag. 115. I argued, that in no good sense it can be true that some of the commands of God about the Sacraments of the Jews contained things belonging to the substance of the Covenant, he tells us pag. 198, 199. of his Defence, that our Sacraments have the same substance with theirs, the same general nature, end, and use; which he makes in these things, theirs were seals of the Covenant, so ours, &c.

But none of all these are to the purpose, his allegations tending only to prove that our Sacraments and the Jews have the same general nature, which he calls substance, but not a word to show that any command about them belonged to the substance of the Covenant. But as if he were angry, or did disdain a man should question his dictates, only recites his meaning, and a passage or two of Protestant Authors, and never answers a word to my objection, Exam. pag. 115. that in no good sense could it be true that some commands of God about the Sacraments of the Jews did contain things belonging to the substance of the Covenant.

Yea when I animadverted on that saying in his Sermon, the manner of administration of this Covenant was first by types, shadows and sacrifices, &c. It had been convenient to have named Circumcision, that it might not be conceived to belong to the substance of the Covenant: I reply, saith he, in his Defence, pag. 99. this is a very small quarrel, I added, &c. which supplies both Circumcision and other things. Which words in the plain construction of them do note, that Circumcision is comprehended in his “&c.” as belonging to the manner of administration, not to the substance of the Covenant. And yet pag. 187. he has these words, I have already proved (that is nowhere, no not so much as in attempt) that Circumcision though a part of their administration did yet belong to the substance (meaning of the Covenant of grace) belong to it, I say, not as a part of it, but as a means of applying it. So uncertain and interfering one another are his speeches about this thing.

And yet this salve he adds is not true in any sense in which the word “substance” may be taken. For if he mean by “applying the Covenant” the signifying Christ to come, or the spiritual part promised, so Circumcision was a Type or shadow, and therefore according to his doctrine belonging to the administration that then was, not to the substance of the Covenant; if he mean by “applying the Covenant” sealing or assuring the righteousness of faith to men’s consciences, neither does this make it of the substance of the Covenant, the Covenant being made before. And though Circumcision had never thus applied it, the substance of the Covenant had been the same, yea the Covenant was the same in substance, according to his own doctrine, 2000 years before Circumcision did apply it to any.

Now I do not conceive any thing is to be said of the substance of a thing, when the thing may be entire without it; so that in this point I deprehend in Mr. Marshall’s speeches nothing but dictates; and those very uncertain and confused.

2. Secondly, says he, pag. 198. When I say that God’s Commands about their Sacraments bind us, my meaning never was to assert, that the ritual part of their Sacraments do remain in the least particle, or that we are tied to practice any of those things, but only that there is a general and analogical nature, wherein the Sacraments of the Old and New Testament do agree, which he thus a little before expresses, my meaning being plainly this, that all God’s Commands and Institutions about the Sacraments of the Jews as touching their general nature of being Sacraments and Seals of the Covenant, and as touching their use and end, do bind us in our Sacraments, because they are the same.

Whereto I reply, that Mr. Marshall supposes the Commands of God are about the general nature of being Sacraments and Seals of the Covenant: which is a most vain conceit, there being no such Command or Institution, there’s no such Command that Sacraments should have the general nature of Sacraments, or be Seals of the Covenant, or that they should signify Christ and seal spiritual grace. These things they have from their nature, as he says, which is the same without any Institution.

The natures, essences and quiddities of things are eternal, invariable, and so come not under Command, which reaches only to things contingent, that may be done, or not be done. Did ever any wise man command to men that man should be a reasonable living body, or whiteness a visible quality, or fatherhood a relation? And to say that God commands Sacraments to seal the Covenant, what is this but to say that God commands himself? For he alone by the Sacraments seals to us the Covenant or Promise of Christ, or grace by him. All Commands of God are concerning what the persons commanded should do, and they must needs be of particulars, not of generals, for actio est singularium, action is of singular persons and things. Though God may command man to think or acknowledge Sacraments to be Seals of the Covenant, yet it were a most vain thing for God to command that Sacraments should be Seals of the Covenant, or to have this general end or use, to seal or signify Christ, and spiritual grace, to us, which belongs only to himself to do by his declaration of his meaning in them. Such Commands as Mr. Marshall imagines, are a mere Chimaera, or dream of his brain.

Secondly, the like is to be said concerning his conceit, that such Commands bind us in our Sacraments; For to bind us is to determine what is to be done, or not to be done by us; But such imagined Commands do not determine what is to be done or not to be done by us, and therefore cannot bind at all.

Thirdly, when Mr. Marshall. confesses we are not tied to the least particle of the ritual part or any practice of those things, he does thereby acknowledge that all the Commands of God about the Sacraments of the Jews, which were all about rituals, are quite abrogated. For all Sacraments are Rites or Ceremonies, and to imagine a Command about a Sacrament, and not about a ritual part or Ceremony, is to imagine a Command about a Sacrament, which is not a Sacrament, Chamier. Panstr. Cathol. Tom. 4. lib. 1. chap. 8. Sect. 9. arguing against Suarez the Jesuit, that dreamed of a Sacrament appointed in the law of nature for remedy of original sin, yet had no determined Ceremony, speaks thus; Sacramentum aliquod insti∣tutum à Deo, Ceremonia nulla determinata à Deo, quis capiat? Sacramentum institui et Ceremoniam non determinari? Aequè dixerit loquutum esse deum, et tamen vocem nullam protulisse, nam aequè Sacramenti genus est Ceremonia et Vox loqisutionis.

Fourthly, were it supposed that there were some Commands about the general nature of Sacraments, binding us, though every particle and practice of the ritual part be abrogated, yet this would not reach Mr. Marshall’s intent, which is to prove the Command of sealing Infants with the initial seal in force, binds. But to seal Infants with the initial seal in force is not of the general nature of Sacraments (for then it should belong to the after seal as well as the initiating) but after his own dictates of the special nature of the initial seal, and so Mr. Marshall’s principle serves not for his purpose.

3. Thirdly, I argued thus, Examen. part. 2. sect. 8.

If we may frame an addition to God’s worship from analogy or resemblance conceived by us between two ordinances, whereof one is quite taken away, without any Institution gathered by precept or Apostolical example, then a certain rule may be set down from God’s word how far a man may go in his conceived parity of reason, equity, or analogy, and where he must stay;

For to use the words of the Author, whose book is intitled Grallæ, if Christians must measure their worship according to the Institution and Ceremonies of the Jews, it is needfull that either they imitate them in all things, or else that some “O Edipus” resolve this riddle hitherto not resolved, to wit, what is moral and imitable in those Ceremonies, and what not.

But out of God’s word no rule can be framed to resolve us how far we must or may not go in this conceived parity of reason, equity, or analogy,

Ergo.

The major is evinced from the perfection of God’s word, and the providence of God to have the consciences of his people rightly guided. The minor is proved by provoking those analogists that determine from the Commands about the Mosaical Rites and usages what must be done or may not be done about the mere positive worship and Church-order of the New Testament, to set down this rule out of God’s word.

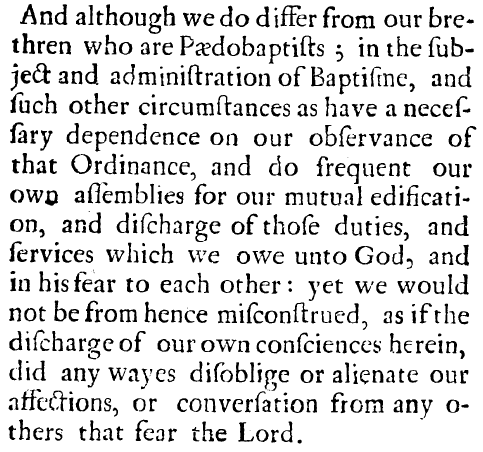

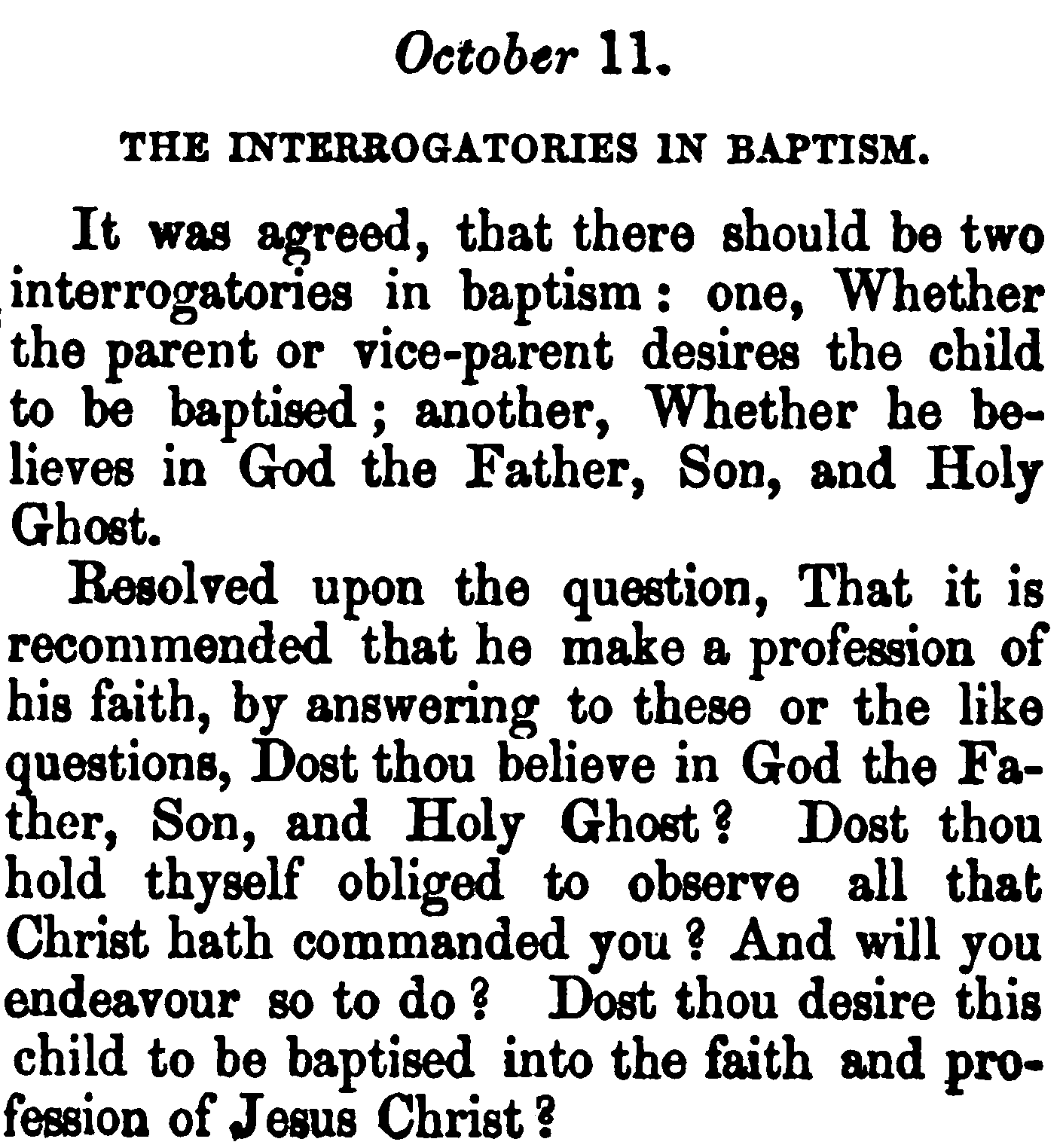

This argument is confirmed by experience in the controversy between Presbyterians and Independents, jarring about the extent of Infant-baptism, the Elders in new England, Mr. Hooker, (besides Mr. Firmin) Mr. Bartlet, &c. restraining it to the Infants of members joined in a Church gathered after the congregational way as it is called. Mr. Cawdrey, Mr. Blake, Mr. Rutherfurd and others extend it farther, master Baxter. Plain scripture proof, &c. chap. 29. part 1. pag. 101. to all whosoever they be, if they be at a believer’s dispose.

And both sides pretend analogy, which being uncertain, Mr. Ball after much debate about this difference, as distrusting analogy, determines thus in his reply to the answer of the new England Elders to the 9. posit. posit. 3. and 4 pag. 38. But in whatsoever Circumcision and Baptism do agree or differ (which is as much as to say, whatsoever their analogy or resemblance be) we must look to the Institution (therefore the Institution of each Sacrament must be our rule in the use of them, not analogy, and analogy is not sufficient to guide us without Institution, and to shew that analogy serves not turn of itself to determine who are to be baptized, he adds) and neither stretch it wider, nor draw it narrower than the Lord has made it, for he is the Institutor of the Sacraments according to his own good pleasure, and it is our part to learn of him, both to whom, how, and for what end the Sacraments are to be administered, how they agree, and wherein they differ, in all which we must affirm nothing but what God hath taught us, and as he has taught us. Which how they cut the sinews of the argument from Circumcision to Baptism, without wrong to master Ball, is shewed in my Apology, Sect. 13. pag. 57.

Mr. Marshall. in his Defence, pag. 83. Mr. Blake pag. 74, 75. of his answer to my letter, seem to deny, that Paedobaptists do frame an addition to God’s worship from such analogy, the contrary whereof is manifest from the passages cited before. But Mr. Blake over and above, pag. 75. sets down three cautions, which being observed, then this kind of arguing from analogy and proportion is without any such pretended danger. The insufficiency of which cautions being shown in my Postscript to the Apology, Sect 17 pag. 143. I conceive it unnecessary to repeat my words.