In this post, I want to investigate the relation of faith to baptism in the Reformed tradition, and how it relates to modern discussions and debates.

Common Argument: Sacraments are God’s word to us, not our word to God

In my experience with debates about credobaptism vs. paedobaptism, one of the common arguments that modern Reformed Christians direct toward Baptists is that Baptists misunderstand the nature of sacraments. The common argument goes like this:

Sacraments are God’s word to us, not our profession of faith to God. Infant Baptism fits this perfectly because it is a picture of God’s grace promised to a helpless individual. Baptists turn baptism into a work performed by man, rather than a sign of divine grace given by God.

Let’s be clear, up front. It would be very easy to provide numerous examples of Baptists laying a heavy emphasis on baptism as man’s profession of faith to God. And it would also be easy to say that in such cases there is an omission and neglect of appreciating sacraments as God’s word to his people. I grant this in full, and Baptists need to do a much better job at teaching and appreciating sacraments as God’s word to his people.

However, do Reformed Christians fall into the same mistake, but on the opposite side? Do they, by emphasizing God’s grace signified to man in the sacraments, neglect and omit man’s side in the use of sacraments? The Reformed of the 16th and 17th centuries did not. But (if experience can be the gauge here) the modern Reformed do, frequently.

The Reformed: Sacraments are Mutual Testimonies

The Reformed of the Reformation and Post-Reformation eras clearly assert a mutuality in sacraments.

John Calvin, for example, defined a sacrament as:

“a testimony of God’s favor towards us confirmed by an outward sign, with a mutual testifying of our godliness toward him.”

John Calvin, The Institvtion of Christian Religion (London: Reinolde Wolfe and Richard Harrison, 1561), fol. 90v. (IV. 13. 1). Cf. also fols. 94v-95r. (IV. 13. 13-14).

And William Perkins offered a similar definition:

“Baptism serves to be a pledge unto us in respect of our weakness, of all the graces and mercies of God, and especially of our union with Christ, of remission of sins, and of mortification. Secondly, it serves to be a sign of Christian profession before the world, and therefore it is called ‘the stipulation or interrogation of a good conscience,’ 1 Pet. 3:21.”

William Perkins, A Commentarie or Exposition, upon the five first Chapters of the Epistle to the Galatians (Cambridge: John Legat, 1604), 249.

And Lucas Trelcatius offered the same:

“By the name of Sacrament, we understand a signe of grace, ordained of God, that he might both seal up his benefits in us, and consecrate us to himself for ever; for in the signification of Sacrament, there is a mutual respect: the one on God’s behalf offering grace; the other on man’s behalf, promising thankfulness.”

Lucas Trelcatius, A Briefe institution of the Common Places of Sacred Divinitie (London: T.P. for Francis Burton, 1610), 293. Spelling updated.

These statements may seem to create a tension with infant baptism. How can an infant participate in the mutuality of the sacrament?

The Reformed: Faith is a Prerequisite for Baptism

For many paedobaptists in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the mutual nature of sacraments was not an obstacle. They did not hesitate to connect baptism with a profession of faith, even in the case of infants. In fact, they required faith for baptism.

One way to handle this was to have sponsors answer for the child. This was the doctrine of the church of England. Sponsors profess faith and repentance for the child. You can read about it in this post.

The Westminster Assembly debated this issue and concluded that it was necessary for parents to make a profession of faith in the baptism of their children. You can read about it in the post just linked above. The Assembly’s decision relocates the profession of faith. It is not the child’s faith professed by sponsors, but the parents’ faith.

The Church of England and the Westminster Assembly were not alone in requiring faith in baptism. Edward Polhill noted that the Leiden Synopsis (its title is Synopsis Purioris Theologiæ, the work of Johannes Polyander, Andreas Rivetus, Antonius Walaeus, and Anthonius Thysius), first published in 1625, likewise required faith in infants prior to baptism.

These are not the views of an isolated or idiosyncratic Reformed writer. The Westminster Assembly and the Leiden Synopsis are collaborative projects of some of the best minds the Reformed faith has ever known. But what does the Leiden Synopsis actually say about baptism, faith, and infant baptism?

The Leiden Synopsis: Infants of the Faithful have the Seed of Faith

I’ve translated relevant portions of Disputation 44, “Of the Sacrament of Baptism.” I don’t claim to be a Latinist, so feel free to check or correct my work in comparison to the original here. This portion of the Synopsis should be released in translation this year.

Though not exactly germane to this discussion, we can note that the Leiden divines makes immersion or pouring an indifferent matter, as well as whether to dip/pour once or thrice.

Thesis 19. And whether the baptizand should be dipped once, or three times, is judged a thing indifferent in the Christian church, as also whether by immersion or aspersion.

Moving on to their theology of infant baptism, here are relevant portions. Edward Polhill’s quote above was referring to Thesis 29.

Thesis 28. No valid distinction can be made between the baptism of adults and infants, except that the baptism of adults is a sign and seal of regeneration already possessed, and the baptism of infants is the instrument of the beginning of regeneration. There is no foundation for any difference beyond this in all Scripture, which acknowledges but one kind of baptism only…

Thesis 29. Therefore we do not align the efficacy of baptism with the moment of its administration, when the body is dipped in the water, but in all persons baptized we do require beforehand faith and repentance, though with the judgment of charity. And this is just as true in the case of covenant infants, in whom, by virtue of the divine blessings and covenant of the gospel, the seed and spirit of faith and repentance are present, we contend, just as in adults, for whom profession of actual faith and repentance is necessary. For as when a seed is cast in the earth, it does not always grow to its height immediately, but [it grows] when rain and warmth come upon it from the sky, neither is the efficacy of the sacramental sign always tied to its first moment, but in the passage of time, with the blessing of the Holy Spirit, is it granted.

Thesis 47. Second, we count [as valid subjects of baptism] infants who are born of faithful and federal parents, according to the promise of God, Genesis 17 “I will be God to you and your seed.” […] To whom the thing signified pertains, no one can deny the sign. […] Now then truly none can deny that the benefits of the blood and Spirit of Christ belong to the infants of the faithful, except those [children] who choose to exclude themselves from salvation; neither is anyone able to enter the kingdom of God unless they are regenerated by water and Spirit, John 3:5. For no one is of Christ who does not have his Spirit, Romans 8:9.

Thesis 48. Ephesians 5:26 is a confirming illustration of this, where the apostle says “Christ loved his church, and gave himself up for her, cleansing her in the washing of water through the word.” From which it follows that the infants of the faithful are not born into a different church from the one for which Christ gave himself, and which he cleansed with the washing of water through the word.

The idea that baptism and faith go hand in hand is not at all a tension for those who believe that the infants of the faithful possess “the benefits of the blood and Spirit of Christ” and have “the seed and spirit of faith and repentance.”

Some Reformed: Infants of the Faithful Have a Distinct, Provisional, Perishable, Regeneration

The doctrine that the infants of the faithful possess the seed of faith creates another tension. What does it mean for covenant children to possess the seed of faith and the blessings and benefits of Christ, and yet “to choose to exclude themselves” from salvation? Also, are the infants of the faithful not born in Adam?

There are varying answers to these questions among paedobaptists. Joseph Whiston lays out various options in this post. Whiston’s option is that the infants of the faithful have a provisional regeneration that is distinct in kind from the ordinary regeneration that believers experience.

For Whiston, and some Reformed, their infants, by virtue of the federal holiness they enjoy as children of the faithful, are cleansed of original sin, and are therefore guaranteed to enter Heaven if they die in their infancy.

For some sources on the discussion and pedigree of such views, see this post, this post, and the related (though later) discussion of sources here:

Conclusions

We can make the following conclusions:

First, the common caricature of “The Reformed make baptism God’s word to us, and Baptists make baptism man’s word to God” demonstrates that both sides need a lesson in historical theology. There is no reason why Baptists should not appreciate and enjoy the sacraments, first and foremost, as God’s promises made visible to his people. Likewise, the Reformed should not hesitate to say that participation in the sacraments is a mutual testimony, from man to God.

Second, related to this, the common caricature that Baptists connect faith too closely to baptism must be applied equally to the Westminster and Leiden divines. They require faith for baptism. It simply isn’t a “Baptist” move. A distinction can be made between fidebaptism, and credobaptism. The Reformed baptize based on faith (fidebaptism), not necessarily profession of faith (credobaptism). However, that would only apply to infants. The Reformed would practice fidebaptism for infants, and credobaptism for adults.

Third, the modern Reformed departure/distancing from (what I perceive as) the more robust forms of paedobaptism explains some of the tensions with so-called “Federal Vision” ideas. Like it nor not, in some cases, certain tenets of the more “Federal Vision” flavor of paedobaptists are not so much a departure from the Reformed tradition as they are a return to one of its more robust forms.

Fourth, modern Reformed Christians need to recognize that the common argument of “We baptize based on the promise to us and our children” is anemic in comparison to “We baptize on the basis of God’s covenant with us, by virtue of which our children are provisionally cleansed and have the seed of faith.” In the modern Reformed version, what is actually true of a covenant child? Promises are made to the child, but is there any way to say, definitely, that any given infant has actual possession of any benefit? I have a feeling that in the social media circles I know, any Reformed Christian who began to assert objective benefits for their covenant children would be swiftly and strongly denounced by other Reformed Christians.

Fifth, the modern Reformed version of paedobaptism creates a tension between infant and adult baptism (to use the Leiden Synopsis’ categories). As the Leiden Synopsis states, its version of infant baptism is very much in line with adult baptism. Both presuppose cleansing; both require repentance and faith. But the common modern Reformed version of paedobaptism makes paedobaptism, as William Cunningham said,

“a peculiar, subordinate, supplemental, exceptional thing, which stands indeed firmly based on its own distinct and special grounds.” (The Reformers and the Theology of the Reformation)

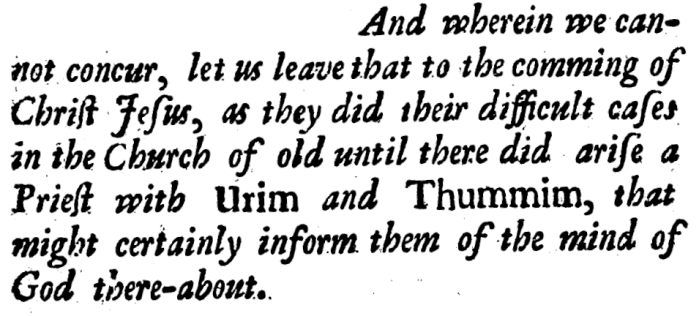

For Reformed Baptists (i.e., 2LCF Baptists), there is, as the Leiden Synopsis states, “but one kind of baptism only” acknowledged by the Scriptures. That is credobaptism, baptism based on profession of faith, not age. Are the modern Reformed ready to embrace the older Reformed credobaptism and bring their adult and infant baptism into realignment? Or will they practice credobaptism for adults, and something else for their children?