In a previous post, I offered three clarifications about historical Particular Baptist covenant theology as a response to Dr. R. Scott Clark’s post dealing with the same matters. Dr. Clark posted a second article continuing the dialogue, and I found it to be a helpful article in that it mined down deeper and thus portrayed more precisely, I think, the details and differences of the parties referenced here (Particular Baptists and the broad Reformed tradition).

Since I am the primary pen being referenced in Dr. Clark’s post, I thought it would be helpful to continue this discussion in an attempt to further the cause of mutual understanding.

Before I quote and respond to a few pieces of Dr. Clark’s recent post, I want to propose to the reader, whether a proponent or opponent of Particular Baptist covenant theology, two things for their consideration before and during discussing or debating these issues.

First, covenant theology, whether considered exegetically or historical-theologically, defies simplification and summary. It deals with, necessarily and unavoidably, the forest and the trees. It covers the entire Bible. Its scope is all of redemptive history. It seeks to explain the purpose of all God’s actions. It is a subject that requires micro and macroscopic perspectives. Not only is this true in the case of studying covenant theology exegetically, but when one adds to this the history of the church’s attempts to handle the subject, i.e., historical theology, the plot thickens considerably. It is therefore a subject whose grammar and vocabulary must be sufficient for the task of dealing with trees and forests. One must exercise great caution and patience in studying a subject of such a scope. And it is therefore a subject not well suited for Twitter, Facebook, and Blogs (like this one).

Second, the Disciples/Apostles got this wrong at first and for some time after the ascension and Pentecost. The Jews got this wrong. Many early Christians got this wrong, provoking church councils and many apostolic epistles in our New Testaments. The Reformed tradition has a great deal of diversity on how the pieces fit together (without denying considerable unity in parts of the subject as well). Tread lightly. Take your time. Don’t be in a rush. Don’t go to war in your first year of marriage.

Now, on to an attempt to offer brief responses of a clarifying nature.

Dr. Clark said,

the PBs do not envision the same sort of administration of spiritual benefits through the external administration of the types and shadows, the various Old Testament administrations of the covenant of grace as the Reformed understand things.

Similarly,

that reception [of the benefits of Christ] has little to do with the actual, external, historical administration of the covenant of grace through types and shadows. For them, the substance of the covenant grace is not the divine promise to be a God to us and to our children but only Christ

As a Particular Baptist, I find these words somewhat confusing. Let me offer the reply, then the explanation. The reply is that we believe that the benefits of Christ are made known and received specifically through the types and shadows. How else were they revealed, received, and enjoyed if not through the Israelite system? So to say “the PBs do not envision the same sort of administration of spiritual benefits through the external administration of the types and shadows” does not fit right, to me.

What’s the explanation? It has to do with one’s view of typology. Particular Baptists believe that types and antitypes are two different, but related, things. God tells us in Hebrews 10:1-4,

1 For since the law has but a shadow of the good things to come instead of the true form of these realities, it can never, by the same sacrifices that are continually offered every year, make perfect those who draw near. 2 Otherwise, would they not have ceased to be offered, since the worshipers, having once been cleansed, would no longer have any consciousness of sins? 3 But in these sacrifices there is a reminder of sins every year. 4 For it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins.

Animal sacrifices are not the blood of Christ and cannot take away sin. But they do teach God’s people about penal substitutionary atonement. And they do make the people long for a more perfect sacrifice by reminding the participants of their sin, i.e., not cleansing their consciences. So then, the animal sacrifice is not the substance of the covenant of grace. It is not the sacrifice of Christ. But it reveals the sacrifice of Christ. And the people of God, combining this with other revelation in other types and shadows trusted in a sacrifice not-yet-offered for them, and enjoyed its conscience-cleansing benefits through the animal sacrifices but not by the animal sacrifices. These verses were what convinced John Owen that the old covenant was not the new covenant, in substance. A covenant that does not take away sins is not the covenant of grace, however much it subserves the covenant of grace.

Furthermore, not only are types not antitypes, but types had their own particular meaning and function in their own original context. When ceremonially unclean, animal sacrifices really and truly restored you to holiness, an outward holiness granted by the old covenant. To skip this initial meaning of a type and jump straight to the revealed antitype is to flatten out typology and transform the old covenant into the new in an unbiblical way. When typology is flattened into outward differences alone, accidental difference, it paves the way for the importation of old covenant practices and details into the new, such as the use of circumcision to justify paedobaptistm. The new is merely the old renewed.

Particular Baptists treat all types the same way (well I do, anyway, and the 17th-century PBs did). Types are not their antitypes. They cannot be their antitypes. They are not the antitypes in a lesser form. They are not the antitypes in an older version. They are not the antitypes in a different outward arrangement. But types are never not types. They exist to reveal antitypes. Though the old covenant can never be the new covenant, it can never stop revealing the new covenant, either.

So then, when Dr. Clark speaks of the external administration of the covenant of grace, we look at typology as the Bible defines it and we say that what he and others call the old external administration of the covenant of grace was actually a distinct but subservient covenant, the old covenant. And yet, because of typological subservience, we agree that the same benefits of the one covenant of grace were revealed, received, and enjoyed by OT saints through the old covenant, but not by the old covenant.

And for this reason I do not recognize this statement, quoted before, “reception [of the benefits of Christ] has little to do with the actual, external, historical administration of the covenant of grace through types and shadows.” It has everything to do with that. But types are not antitypes. Goat and bull blood is not the blood of the Son of God.

Typology deserves and demands a much more detailed treatment. But alas, we are currently trapped in blogland. Moving on, Dr. Clark says,

There is not a single Reformed theologian of whom I am aware, certainly not in the classical (confessional) period, who affirm the doctrine that there is a substantial difference between the New Covenant and the covenant of grace as administered in Old Testament types and shadows.

This brush is too broad to be helpful in this case. Why? First, there were (and are) many Reformed theologians who affirmed that there is a substantial difference between the new covenant and the Mosaic covenant. So then, the “not a single Reformed theologian” language is a cloak covering an inconvenient diversity. Granted, I am likewise not aware of Reformed theologians who affirmed that the new covenant is distinct from the Abrahamic covenant in substance. But that is quite different from the language used above. Second, the language is unhelpful in that it seems to imply that Particular Baptists believed in a substantial difference between the new covenant and the covenant of grace in the old testament. That just wouldn’t make sense. So then, while the language sets out to portray two distinct parties, neither description really fits as far as I can see.

Dr. Clark says,

So here is a difference between the PB and the Reformed. For the PBs, the OT covenants are not the covenants of grace as much as they are witnesses to the covenant of grace. For the Reformed the OT covenants are earthly, historical, real, external, administrations of the one covenant of grace through types and shadows. Through those administrations God the Spirit gave more than “external and typical” (typological) blessings. God the Spirit was sovereignly operating within his people through the sacrifices, through the ceremonies, through the prophetic Word, to bring the elect to new life and to true faith in Jesus the Messiah. This is our understanding of Hebrews 11 when it says that Moses preferred Christ—not typical and external blessings—to the riches of Egypt (Heb 11:24–26). Abraham was looking for a city whose builder and maker is God (Heb 11:10). Had he wanted “earthly and typical” blessings, he could have had them.

My explanation of typology above applies to these comments. So all I want to say here is that it seems odd to me to state the Reformed view of the OT saints’ enjoyment of the benefits of Christ as though that is somehow different or distinct from the Particular Baptists’. There is no difference on that point, as mentioned in my previous post and above in this post. So, to raise it as an apparent difference sends strange signals that will likely be interpreted wrongly by those who see the post as a critique of Baptists and the operative differences between us.

Dr. Clark says,

For the Reformed the OT covenants were more than witnesses to and revelations of the covenant of grace, they were administrations of the substance of the covenant: “I will be a God to you and to your children,” the fulfillment of which was Christ, in whom all the promises of God are yes and amen (2 Cor 1:20).

Here is a difference between us is in regard to identifying and defining the substance of the covenant. Insofar as the substance of the covenant of grace is defined as “I will be a God to you and your children” we disagree strongly (and I would argue that this definition does not represent the fullness of Reformed covenant theology). The substance of the covenant of grace is “I will remember your sins no more.”

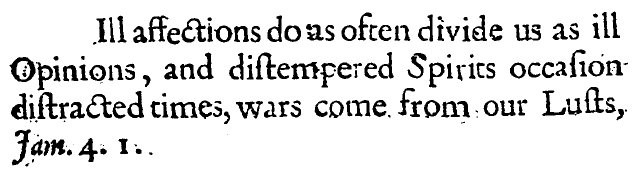

In conclusion, there is a need for more work on both sides, especially in being slow to speak and quick to listen. Particular Baptists need to publish more literature in exegetical theology and historical theology. Paedobaptists need to read that literature as we read theirs. And both sides need to pursue verity more than victory.

As a student of the debate in the seventeenth-century, I lament the divide. Whenever I hear of someone moving from one side to the other, I am sad the divide exists. There can be no victory parade when brethren are the “enemies.” Woe is me, woe is us. Thomas Manton remains quotably helpful.