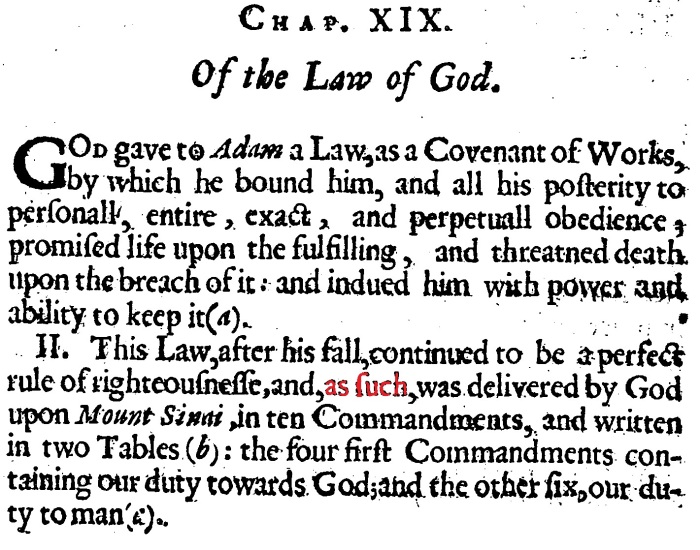

In the previous two posts, we have looked at the distinction between form and matter. The first post dealt with this distinction in relation to the republication of the law of the covenant of works in the Mosaic covenant. The second post dealt with this distinction more broadly, and showed the direction that the Particular Baptists would take this distinction in order to say that though the promise of the new covenant (the gospel) was made known in all of redemptive history, it was not formally established as a covenant until Christ’s death.

To refresh, in light of the formal/material distinction, just because the law is present in a given covenant, it does not mean that this covenant is the covenant of works. Conversely, just because the promise (the gospel) is present in a given covenant, it does not mean that this covenant is the covenant of grace.

In this post, I want to continue along similar lines in order to show the differences between Particular Baptist federal theology and that of their Paedobaptist brothers. I want to do this by showing how the same argumentation was employed, only with completely opposite arguments.

Let’s begin with the Paedobaptists.

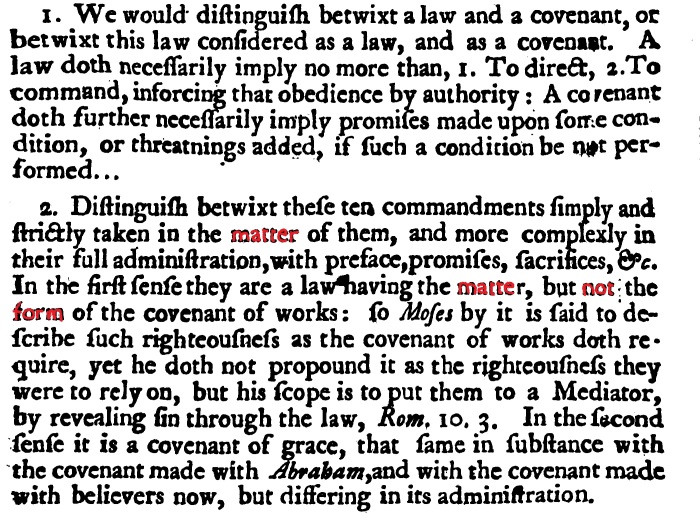

Peter Bulkley argues that although the law of the covenant of works was revealed to Israel in the Mosaic covenant, the Mosaic covenant was not a covenant of works. Why? Because the Mosaic covenant was established on different terms and conditions than the covenant of works. For Bulkley, the Mosaic covenant was an administration of the covenant of grace. In fact, it was the covenant of grace.

Notice the argumentation: the law of the covenant of works, i.e. its material basis, was revealed to Israel, but it was not the basis for their covenant.

William Bridge makes the same argument. He begins with the same foundation of the substance/administration distinction. The Mosaic covenant is the covenant of grace.

In the Mosaic covenant, the covenant of works is declared, but the covenant of grace is actually made.

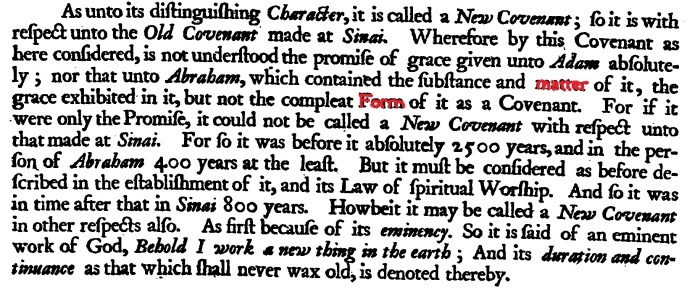

The Particular Baptists employed the same argumentation with opposite arguments. They argued that the promises of the new covenant were revealed and made known from Genesis 3:15 onward, but they were not the material basis for a formal covenant until Christ spilled his blood. The new covenant was truly new. No covenant leading up to it had been established on the promise of eternal forgiveness of sins. All of the covenants of the Old Testament contributed to the progressive revelation of the new covenant, but they were not the new covenant in and of themselves. The new covenant was established on better promises, which meant that it was established on different promises which meant that it was a different covenant.

Nehemiah Coxe gives us an example of the covenant of grace being revealed without being formally made or transacted.

Christopher Blackwood argues that the new covenant is promised but not covenanted in Genesis 17.

Isaac Backus makes the same argument.

This argumentation has been called “promise and promulgation.” The new covenant is promised, but not promulgated in the Old Testament. It exists in its promises alone. This aligns perfectly with the formal/material distinction because both sides will agree that the material basis of another covenant can be revealed and made known independently in a given covenant without becoming a formal covenant. In other words, the law can play a role in the covenant of grace without turning it into a covenant of works for believers. Likewise, the gospel can play a role in the old covenant without turning them into the covenant of grace.

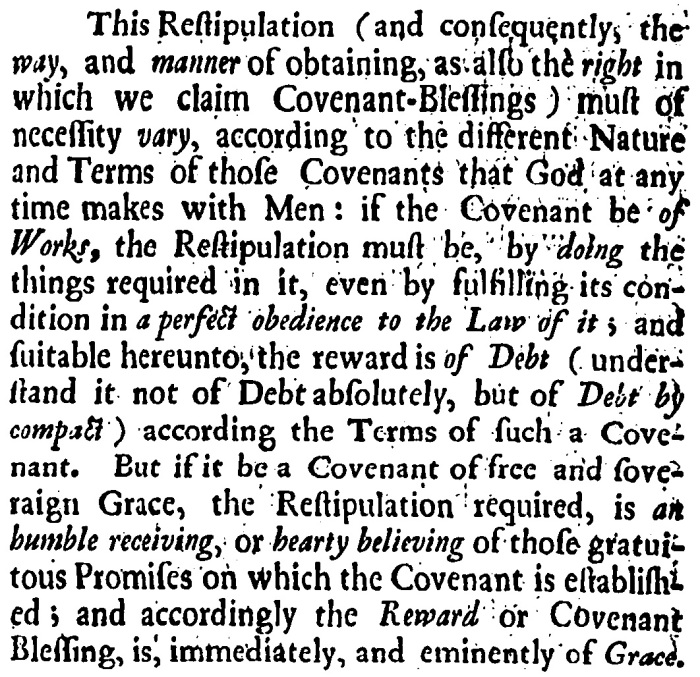

An anonymous Particular Baptist focuses on the betterness of the new covenant’s promises.

Samuel Fisher highlights the meliority “betterness” of the new covenant’s promises.

These excerpts help to highlight the similarity in argumentation alongside of the dissimilarity in arguments between the Particular Baptists and their Paedobaptist brothers. Both sides argued that the law and gospel run through all of the covenants of the Old Testament.

The Paedobaptists were happy to argue that the law was revealed and made known in certain covenants without those covenants being covenants of works. The Old Testament covenants played roles within the two administrations of the covenant of grace.

The Particular Baptists argued that the old covenant was a covenant of works for life in Canaan. It was a covenant that perfected no one’s conscience because it forgave no one’s sins. The new covenant, revealed from Genesis 3:15 onward, was the covenant of grace formally established on the material basis of the promise of forgiveness of sins in Christ’s blood. It was established on different promises, better promises, everlasting promises.