To add a little more to the previous post on formal and material republication, let me fill out how the distinction between form and matter works on a larger scale.

When it comes to justification, the material basis of a covenant is either law or promise. Works/law and grace/promise do not intermingle.

If two parties are committed to each other based on a law, a covenant of works has been established. If two parties are committed to each other based on a promise, a covenant of grace has been established. The matter dictates the form.

In light of this distinction, just because the law is present in a given covenant, it does not mean that this covenant is the covenant of works. Conversely, just because the promise (the gospel) is present in a given covenant, it does not mean that this covenant is the covenant of grace.

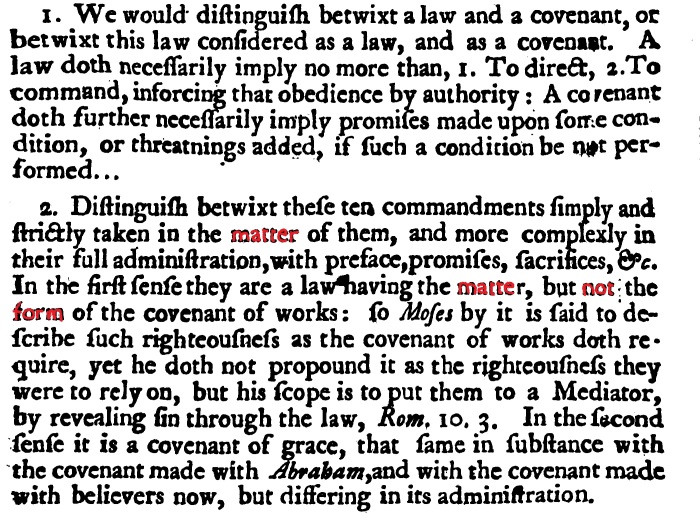

James Durham demonstrates the difference between a law, and a law used to established a covenant of works.

In this line of thinking, Obadiah Sedgwick argues that although the law was present in the Mosaic covenant, it was not a formal covenant of works. This is material republication (as was Durham above).

This also applies to believers. In the Marrow of Modern Divinity, Edward Fisher wanted to protect the idea that although the law came to believers, it did not come as a covenant of works. Legalism is inevitable if we are convinced that the law necessarily entails a covenant of works.

Now, how did this play out in Particular Baptist theology? John Owen will be our theologian. Nehemiah Coxe considered Owen’s work on Hebrews to be representative of his own views on covenant theology.

First, Owen is operating within the same ideas and makes the same points made above, that we have to distinguish between the law on its own and the law as a covenant.

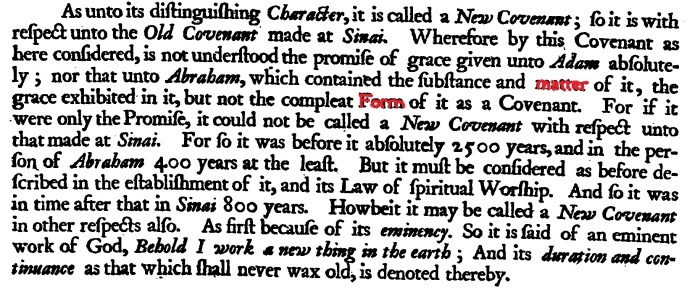

The same is true for the promise of the gospel. Just because the promise of the gospel is present from Genesis 3:15 onward, it does not follow that the covenants wherein it appears are the covenant of grace. Owen argues that the covenant of grace was only a promise until its formal establishment in the new covenant. The elect were saved by virtue of the covenant of grace (the promise of the gospel) in all the ages, but it was not formally established until Christ’s death.

The same point is made again, showing how the New Covenant could not be new if it had already been formally established.

The law and the gospel (the promise) are present in the Abrahamic, Mosaic, Davidic, and new covenants.

Westminster paedobaptists will argue that all of these covenants were established on the promise of the gospel and thus were covenants of grace, or rather a twofold administration of the covenant of grace. The law played the same role in all of them, namely as a rule of righteousness (more burdensome in the OT). None of those covenants were covenants of works.

Particular Baptists will argue that although the promise of the gospel was present and revealed in all of the OT covenants, they were not the covenant of grace. The old covenant saved no one because it was a covenant of works for life in Canaan. Until the New Covenant was formally established in Christ’s blood, the covenant of grace existed in promise form only. The new covenant is truly new, the fulfillment of everything promised and hoped for in redemptive history. No covenant was formally established on the promise “I will remember your sins no more” until the blood of Christ inaugurated the new covenant.

Reblogged this on My Delight and My Counsellors.

Reblogged this on The Reformed Berean.

Reblogged this on 1689reformed baptist/1689bautista reformada.