History is tricky, as is historical theology. We approach old texts and events with modern questions, modern categories, and modern modes of thinking. In the case of discussions about the relation of the Baptistic Congregationalists (i.e., early Particular Baptists) to the Reformed tradition, the same problems present themselves. Do we understand them in their own historical and ideological context? Are they subjects, teaching us who they were and how they thought, or are they objects on whom we impose our modern selves?

The modern age has its advantages, one of which is wide availability of older texts and sources, which means that more and more, we have the opportunity to become familiar with historical individuals or groups from their own literature. This blog has always been dedicated to putting original sources in the view of those interested in them.

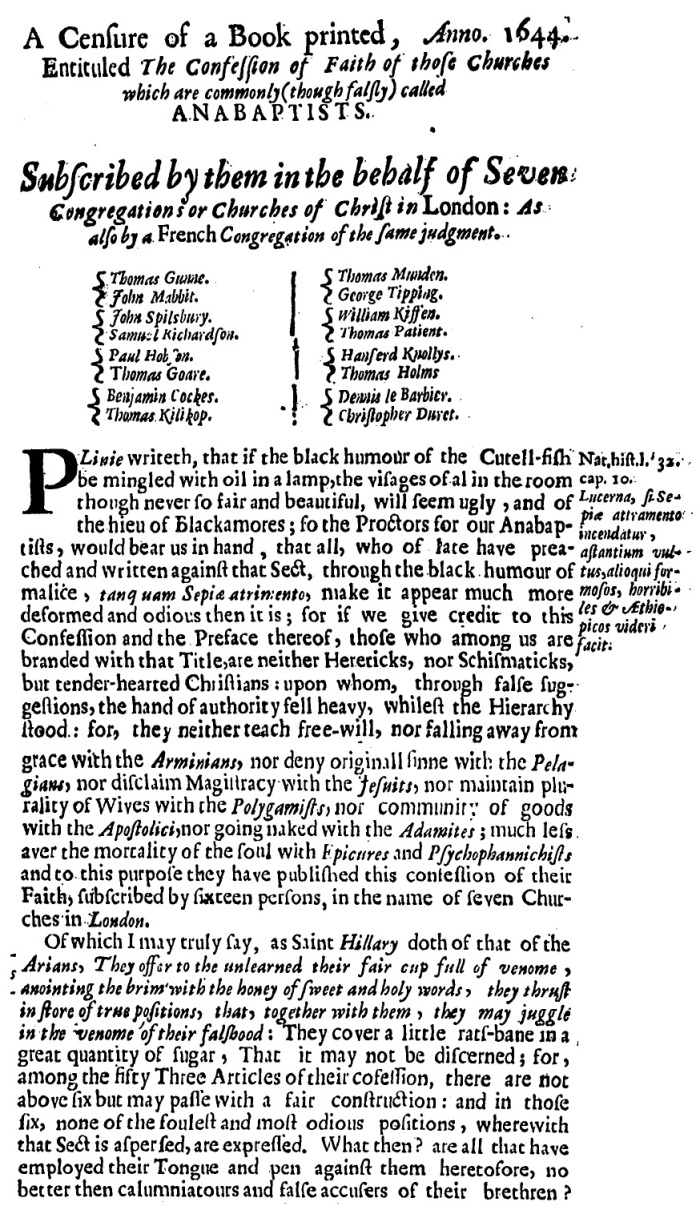

This post focuses on a small publication from William Kiffen in 1645, entitled “A Briefe Remonstrance of the Reasons and Grounds of those People commonly called Anabaptists, for their Seperation, &c. Or Certain Queries Concerning Faith and Practice, propounded by Mr. Robert Poole; Answered and Resolved by William Kiffen.” I want to emphasize the timing of this discussion and how that affects our perception of the Baptistic Congregationalists and their relationship to Reformed churches and christians at that time. Specifically, consider that at this time the Baptistic Congregationalists had published their Confession of Faith, but the Westminster Confession did not yet exist. The Confession, and its related documents were in process, not only in process with regard to the Assembly itself, but also with regard to Parliament approving or disapproving said documents.

The setting of the discussion below is that Robert Poole’s (who appears to be a Presbyterian) daughter Elizabeth and at least one of his servants joined William Kiffen’s church. Robert was very displeased by this and wrote to Kiffen about “my deluded ones” demanding that Kiffen “discharge them, and leave them to the power of me, who have the charge of them.” Poole sent five queries to Kiffen, asking Kiffen to justify the practice of his church in separating from the established church.

My interest is in Kiffen’s response to the accusation made against him and his church of following “the Anabaptistical way” as opposed to the practice of “the Reformed Churches.” I have transcribed portions from this document which you can read below with updated spelling and some updated punctuation. [Bracketed portions are my own insertions for clarification.]

Poole’s First Query

“By what warrant of the word of God, do you separate from our congregations, where the word and sacraments are purely dispensed?”

Kiffen’s Response

“…For do you not daily admit and suffer to be amongst you such as do according to God’s word, leaven the whole lump, 1 Cor. 5:6, and do not purely dispense the word upon them for their healing? The Spirit of Christ saith, such glorying is not good, and the feast of the Lord ought not to be kept with them: and I pray you show me what gospel institution have you for the baptizing of children, which is one of your great sacraments amongst you; what can you find for your practice therein, more than the dirty puddle of man’s inventions affords. And therefore when your sacraments are purely administered according to the pure institution of the Lord Jesus; and when you have dispensed the Word and Power of Christ, for the cutting off all drunkards, fornicators, covetous, swearers, liars, and all abominable and filthy persons, and stand together in the faith, a pure lump of believers, gathered and united according to the institution of Christ, we (I hope,) shall join with you in the same congregation and fellowship, and nothing shall separate us but death.”

Analysis

Remember that Parliament called the Westminster Assembly to reform the national Church of England. Kiffen is responding to such a church, a church where everyone in the parish comes to bring their child for baptism, and everyone in the parish receives the Lord’s Supper. Kiffen denies the purity of the administration of the sacraments based on the impurity of the recipients and the lack of discipline against them.

Arguably, one’s experience would vary from parish church to parish church. Denying the Lord’s Supper to the “abominable and filthy” persons was one of the main issues in priests’ minds in the early decades of the seventeenth century. The “Puritan” movement clashed with the established church over issues such as this. However, Kiffen is correct that the national church as then established was set up in such a way as to receive everyone to baptism and the Lord’s Supper. The Westminster Assembly debated this issue and concluded that parishioners must make a profession of faith in order for their child to receive baptism.

The point at hand is that we see that the Baptistic Congregationalists would not mingle with the “Reformed” churches because at that point in time the nation of England and its Church were undergoing massive social, political, and religious changes. But it was still a national church filled with anyone and everyone.

Poole’s Second Query

“By what Scripture warrant do you take upon you to erect new framed congregations, separated to the disturbance of the great work of Reformation now in hand? [i.e., the Westminster Assembly and the reformation of the national church]”

Kiffen’s Response

“Answer: This query has in it these two parts: 1. That we erect new framed separate congregations. 2. We do, by this, disturb the great work of Reformation now in hand.

To the first, it is well known to many, especially to ourselves, that our Congregations were erected and framed as now they are, according to the rule of Christ, before we heard of any Reformation, even at that time when Episcopacy was in the height of its vanishing glory…even when they were plotting and threatening the ruin of all those which opposed it, and we hope you will not say we sinned in separating from them whose errors you now condemn, and yet if you shall still continue to brand us with the names of Anabaptists, Schismatics, Heretics, etc. for saving ourselves from such a generation (Acts 2:40) as you yourselves have cut off, and from such a superstitious [“superstitious” means doing religious things without scriptural warrant] worship as you say shall be reformed; we conceive it is your ignorance, or worse, and though you condemn us, Christ will justify us even by that word of his, which he hath given us, and we desire to practice, and have already commended to you in that conclusion of our answer to the first query.

And for the second part of your query, that we disturb the great work of reformation now in hand; I know not what you mean by this charge, unless it be to discover [reveal] your prejudice against us, in reforming ourselves before you. For as yet we have not in our understanding seen, neither can we conceive anything of that [which] we shall see reformed by you according to truth, but that through mercy, we enjoy the practice of the same already; ’tis strange this should be a disturbance, to the ingenious faithful Reformer; it should be (one would think) a furtherance rather than a disturbance

And whereas you tell us of the work of Reformation now in hand, no reasonable men will force us to desist from the practice of that which we are persuaded is according to the truth, and wait for that, which we know not what it will be; and in the meantime, practice that which you yourselves say must be reformed: but whereas you tell us of a great work of reformation, we should entreat you to show us wherein the greatness of it consists, for as yet we see no greatness, unless it be in the vast expense of money and time for what great thing is it to change Episcopacy into Presbytery, and a Book of Common Prayer into a Directory, and to exalt men from living of £100 a year to places of £400 per annum? For I pray you consider, is there not the same power, the same priests, the same people, the same worship, and in the same manner still continued, but when we shall see your great work of reformation to appear, that you have framed your congregations according to that true and unchangeable pattern, 1 Cor. 3.9-11 according to the command of our Savior, Matt. 28:19-20 and the Apostles’ practice, Acts 2:41; 5:13-14 and made all things suitable to the pattern, as Moses did, Exod. 25:40; Heb. 8:5 you will see, I hope, that we shall be so far from disturbing that work, as that we shall be one with it.”

Analysis

Kiffen argues that the Baptistic Congregationalists cannot be accused of separating from the work of reformation in England when they separated and formed their congregations during the time of Episcopacy. And if the Assembly and others are convinced that many features of the Church of England need to be abandoned and reformed, why should the Baptistic Congregationalists be criticized and called “Anabaptists, Schismatics, and Heretics” for already having done so?

It is very interesting that Kiffen points out that the Baptistic Congregationalists cannot be blamed for remaining separate from the national church during this time of Reformation when it is not clear what the end result will be. And if the Baptistic Congregationalists are already convinced that their churches are biblically grounded, and the Assembly acknowledges that the national church in its present form is in need of reform, why would the Baptistic Congregationalists not remain as they are and wait to see what happens?

In other words, the Baptistic Congregationalists were not rejecting the Reformed church in England. They were witnessing the development of something incomplete and, to them, unhopeful. Kiffen vows unity if the end result is acceptable. But he sees the direction that the Assembly is going and doesn’t see much difference with the Anglican establishment. National uniformity (the Directory) and nationally supported ministers (the tithe) in a national church that includes everyone (infant baptism) seems quite the same as it always had been. Kiffen was not the only one. Milton’s famous lines echoe here,

Poole’s Fifth Query

“How can you vindicate by the word of God, your Anabaptistical way, from the sinful guile of notorious schisme, and dissection from all the Reformed Churches?” [Read “guile” in the sense of an accusation of treachery.]

Kiffen’s Response

“Answer: They that run may read what fire this pen and heart was inflamed withall in the writing and indicting this query; but first of all, if by Reformed Churches, you mean those churches planted by the Apostles in the Primitive times, which are the platform for all churches in all ages to look unto, to be guided by these apostolical rules left [for] them; then we shall vindicate by the word of God our Anabaptistical way, as you are pleased to call it, from that guile.

And first, although we confess ourselves ignorant of many things, which we ought to know and desire, to wait daily for further discoveries of light and truth, from him which is the only giver of it to his poor people, yet so far as we are come, we desire to walk by the same rule they did. And first of all, we baptize none into Christ Jesus, but such as profess faith in Christ Jesus, Rom. 6:3 by which faith they are made sons of God, and so having put on Christ, are baptized into Christ, Gal. 3:26-27 and that Christ has commanded this, and no other way of baptism, see Matt. 28:19; Mark 1:4-5; Luke 3:7-8 and that this also was the practice of the Apostles, see Acts 2:41 and 8:12, 36-37; 10:47-48. And that being thus baptized upon profession of faith, they are then added to the church, Acts 2:41 and being added to the church, we conceive ourselves bound to watch over one another, and in case of sin, to deal faithfully one with another according to these Scriptures, Levit. 19:17-18; Matt 18:15 and if they remain obstinate, to cast them out, as those that are not fit to live in the church, according to that rule, 1 Cor 5:4-5; Matt 18:19-20 by all which, and many other particulars I might name, it appears through mercy, we can free ourselves from that guile.

And truly, if your eyes were opened to peruse your own practices and ways, you would then see we could better free ourselves from that notorious guile of schism from those Reformed Churches, then you can free yourselves from the notorious guile of schisming from Rome; For 1. You hold their baptism true, their ordination of ministers true, their maintenance by tithes and offerings true, their people all fit matter for a church, and so true, and yet you will separate from them for some corruptions. Now, for our parts, we deny all and every one of these amongst you to be true, and therefore do separate from you; so then, when you have made satisfaction for your notorious schism, and return as dutiful sons to their Mother, or else have cast off all your filthy rubbish of her abominations which are found amongst you, we will return to you, or show our just grounds to the contrary.”

Analysis

Kiffen argues that he is more concerned with framing his church according to the practice of the Apostles in the New Testament than to any church at any point in history. So, though not quite saying it clearly, he argues that the title “Reformed” can only ever truly apply to those that have reformed their doctrine and practice by the pattern and commands of the Apostles. Based on this foundation, Kiffen summarizes their practice, with Scripture proofs, which is essentially his way of saying, “We are reformed according to the word of God.”

But the “nitty gritty” (read in Nacho Libre’s voice) shows up when Kiffen points Poole back to the “Reformed Churches” and accuses them of containing remnants of Roman Catholic theology. According to Kiffen, the Baptistic Congregationalists regarded the following features of the “Reformed Churches” in England during this time of ongoing Reformation as false:

Infant baptism. It was administered to the wrong subjects, and with the wrong mode.

Ordination of ministers. They were ordained by presbyteries (or previously by bishops), but not congregations. Congregations had a right of refusal, but not ordination. On the Westminster Assembly’s involvement in stocking the pulpits of the national church, see this excellent book.

Tithes and offerings. Baptistic Congregationalists believed that believers were obligated by moral equity and positive command to give to the church for the support of the minister and the poor. But they denied that the tenth could be required, and they especially denied that it could be extracted from the nation.

The matter of the church [that of which it is comprised]. A national church is made up of a nation. The Baptistic Congregationalists, as Kiffen had expressed, only received professing believers as members. Yes, as mentioned above, the Assembly required a profession of faith for baptism and you can see exactly what kind of profession in that post. But remember the timing of this discussion. Such things were still in process in the Assembly. And even with such a profession at play, the vision of the church is still a national one, which Kiffen would have rejected.

Kiffen uses these points to say that the Baptistic Congregationalists should not be criticized for separating from “the Reformed Churches” when they regard such features of said churches as false, while “the Reformed Churches” separated from Rome despite regarding such features of the Roman church as true.

Conclusion

To sum up, we see several helpful historical contextualizing conclusions.

- The Baptistic Congregationalists “separated” from the national church before it was ever in a process of “reformation” and were unwilling to reintegrate with it while its “reformation” was still in progress. They did not separate from the Reformed churches as Reformed churches.

- Their refusal to reintegrate with the church while “reformation” was underway, their congregational independence (e.g., ordaining their own ministers), and their limitation of baptism to professing believers earned them the label “Anabaptists, schismatics, heretics, etc.” But they denied such terms and defended their beliefs and their practices here and elsewhere.

- The theological identity of “the Reformed churches” in England was unsettled at that time. The minutes and papers of the assembly show that the Assembly included a wide variety of views on many different doctrines. Some of those differing views were antithetical to one another in practice, such as church polity or liberty of conscience in matters of religion. The end result could have looked very different, if the opposite competing voices had prevailed.

- The Baptistic Congregationalists were not optimistic about the Assembly’s “work of reformation” because they saw it maintaining a national church without liberty of conscience in matters of religion.

- At the time of this discussion, Kiffen saw serious flaws in the features of the national church. But they are all practical ecclesiological features: paedobaptism, ordination, tithes, and membership. This practical separation should not distract us from the substantial doctrinal agreement that yet remained. Consider the fact that Kiffen is taking a “wait and see” approach to the Assembly, and that Kiffen and others were more than willing to incorporate the vast majority of the Westminster Confession (inherited through the Savoy Declaration) into their Second Confession of Faith in 1677. He was not rejecting the theology of “the Reformed churches” wholesale. He simply could not, in practice, join with the church as it was then constituted, and according to the vision he saw it pursuing.

These conclusions and the preceding material shed historical light on the ideas and labels being used in the 1640s when the Baptistic Congregationalists were growing and establishing themselves. If we approach them with questions like “Were they Reformed churches” or “Did they reject the Reformed churches” or “How did the Reformed churches respond to them” or “Why did the Reformed churches call them Anabaptists” we will struggle to answer those questions accurately apart from attention to sources such as this coupled with historical and chronological sensitivity. Or, we might find that such questions simply don’t work.

Our modern context and labels simply don’t map onto 1640s England. And we rarely think about them (or read them) properly.

We need to develop a more nuanced vocabulary that can describe, with as much accuracy as possible, a context as complex as England in the seventeenth century in general, or the 1640s in particular.*** Such an approach is modeled and developed in Matt Bingham’s book, Orthodox Radicals, an apt title for one such as Kiffen who was orthodox in his theology but appeared entirely radical and was therefore unwelcome at the Poole Party.

***Good luck.