In the ongoing discussion of the historical and theological origins of the Particular Baptists, R. Scott Clark recently pointed to doctrinal agreement between Particular Baptists and Anabaptists. He referred the reader to a book, which I would also highly recommend. It is important to read others’ writings, to give them an opportunity to explain themselves beyond the bits and pieces of tweets, so I thought I would follow up on the suggestion and consider interacting with the argument found within.

In the work referenced in the tweet above, one of Clark’s arguments is that the Reformed have a united covenant theology expressed in their Confessions of Faith, and that the Particular Baptists embraced the Anabaptists’ covenant theology rather than that of the Reformed.

“Bingham’s analysis ignores one very significant way in which the Particular Baptists agreed with the Anabaptists, on the nature of the covenant of grace and baptism.” (Page 75)

“In short, despite the substantial identity between the Particular Baptist confessions with the Reformed on several important points, at essential points, the Particular Baptists confess a different reading of redemptive history, one that has more in common with the Anabaptists than it does the Reformed.” (Page 80)

“Indeed, there are precious few things on which all the Anabaptists agreed except their anti-Protestant soteriology and their view of the covenant of grace and baptism, the last of which the Particular Baptists have adopted.” (Page 84)

To prove the claim, Clark surveys the references to covenant in 1LCF and 2LCF and notes that they decline to confess the standard Reformed model of one covenant of grace under multiple administrations. This is, of course, true. But what arguments can be drawn from this? Does a brief appeal to 1LCF and 2LCF and the absence of that language substantiate the argument that the Particular Baptists “adopted” the Anabaptists’ view of the covenant of grace, or that they have “more in common with the Anabaptists” on this point? Clark does not offer any sources to make the comparison.

In response, the Particular Baptists’ covenant theology sprouted from the unity and diversity of Reformed covenant theology. There was a strong branch of Reformed covenant theology that affirmed that the Mosaic covenant was not the covenant of grace, in substance, because it operated on the basis of works and curses. They taught that these differences subserved the covenant of grace by pointing and pushing Israel to Christ. Some among the Reformed were willing, therefore, to identify in redemptive history a subservient covenant based on obedience, a covenant that was not the covenant of grace, in substance.***

Such views flourished in the Congregationalist churches, which were the nursery of the the Particular Baptists. Some of those Congregationalists extended the argument and became convinced that the same reasons applied to the Abrahamic covenant. It was a covenant of obedience, subservient to, but substantially distinct from, the covenant of grace. These are the Particular Baptists. At the same time, some Church of England ministers became convinced of the same arguments and joined with those who had emerged from the Congregationalists. These are the Particular Baptists.

Where did they get their covenant theology? From the diversity of the Reformed covenant theology tree. Notably, you will not find a single Anabaptist author quoted in Particular Baptist treatises on covenant theology (or any reference to any Anabaptist author at all in any Particular Baptist book that I am aware of), whereas you will find regular citations of Reformed authors as support for their beliefs. Where are they getting their covenant theology from?

I criticize Clark’s lack of sources as proof, so where is my proof? These arguments are presented at length in my book, From Shadow to Substance.

We find then, that Clark’s argument that the Particular Baptists “adopted” the Anabaptists’ model of the covenant of grace, or had “more in common” with the Anabaptists, or “confess a different reading of redemptive history” to be incorrect and unsubstantiated by the historical and literary evidence. Such arguments ignore the trajectories of the diversity of Reformed covenant theology as well as the historical origins of the Particular Baptists.

Now let us be as fair and charitable as possible. When we say that the Particular Baptists argued (with one confirmed exception and perhaps more) that the Abrahamic covenant was not the covenant grace, they really are departing from a Reformed consensus on that point. It is a real difference. It is the difference. This is what made them who they were as a theological group, after all. And if, in Clark’s mind, this is sufficient to banish them from the Reformed Tree-Fort, then so be it.

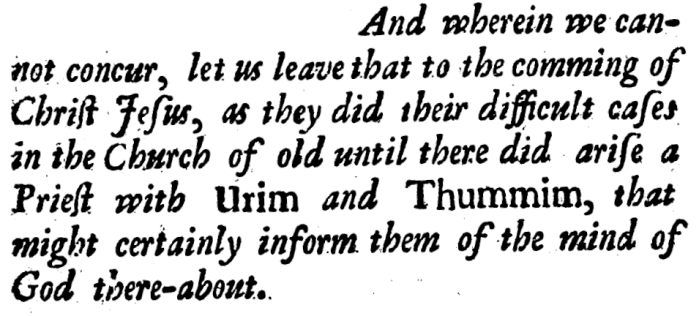

But before we go that far, let us reconsider 1LCF and 2LCF, which Clark noted do not confess the common model of Reformed covenant theology. What do they confess? In short, they confess that the elect are saved by the covenant of grace.*** 1LCF hints at a Pactum Salutis standing behind this. 2LCF makes the pactum salutis explicit. In this, they are confessing the core of Reformed covenant theology, the unity of Reformed covenant theology. And they don’t go beyond that. What I am getting at is that I can sincerely say that Clark, and all Reformed Christians, should be able to confess 2LCF 7.1-3 without any disagreement about what is said. It is in what is not said that we disagree. As evidence, compare 2LCF 7.3…

…with what William Perkins said in his exposition of the Apostles’ Creed in 1603.

2LCF ch. 7 does not advance a specifically “Baptist” position. It affirms a Reformed position.

I therefore appeal to Dr. Clark to change his language in this way:

“The Particular Baptists did not arise from the Anabaptists, nor do their writings show evidence of the influence of Anabaptist sources. The Particular Baptists emerged primarily from the Congregationalist wing of Reformed theology in 1630s and 1640s England. Their Confessions do not deny the Reformed doctrine of the covenant, but do not confess it in the fullness with which it was normally confessed. Their version of covenant theology is an extension of a branch of the Reformed diversity on that point. That being said, they took a step too far by denying the Abrahamic covenant to be the covenant of grace, though they did not place this commitment in their Confessions of Faith.”

One may not think that we belong in the Reformed camp, but one cannot ignore the historical record and sources. One may disagree with another, but can we not speak of those who differ from us in words they accept and understand as representing themselves? Are we not creating unnecessary and harmful barriers through the use of language and titles that do not match the sources, language that others consistently deny represents them? Conceding these matters is part history and part charity. There is no hostile takeover happening. There is a sincere desire for the recognition and acceptance of common genealogy.

I hope that we can all concur that we enjoy much more in common with R. Scott Clark and other Reformed Christians than we ever would with the Anabaptists, even in covenant theology.

***Ironically, this is R. Scott Clark’s view:

This means that his understanding of covenant theology is the closest to ours in the diversity of Reformed covenant theology. All we would say is “On top of the C o G Yahweh temporarily superimposed the Abrahamic-Mosaic-Davidic nat’l cov.” This helpfully illustrates that we are different, but not as different as Clark often makes it seem.

***I, myself, and others have at times overemphasized what 2LCF 7.3 says, reading into it the literature behind it. That must be done carefully. The literature may explain why certain things were not said, but we must not automatically read the literature into what was said. I try to offer a more balanced presentation in my book, From Shadow to Substance.