Recently I have been reading this excellent work by Andrew Woolsey. In one section on the primary sources behind the Westminster Confession of Faith, Woolsey shows the strong influence of John Ball on the confession in general and chapter seven in particular. What I want to point out is the concept of covenantal merit at play in paragraph one of the Westminster Confession and the London Baptist Confession. The two confessions are very similar here.

The Westminster Confession speaks broadly by saying that God’s creatures, though they be obligated to obey God as creatures unto their Creator, could expect no reward whatsoever for their obedience. Yet because God voluntarily condescended to make promises to men, he did so by way of covenant. The London Confession follows the Savoy Declaration by narrowing the focus to the reward of life in particular. But the same principle is operative in both, the principle of covenantal merit. In other words, man’s natural obedience due to God according to the law of nature in no way obligated God to give anything to man. Man’s natural obedience was not intrinsically meritorious. The texts cited in support of this are significant.

Luke 17:10 “So you also, when you have done all that you were commanded, say, ‘We are unworthy servants; we have only done what was our duty.'”

Job 35:7 “If you are righteous, what do you give to him? Or what does he receive from your hand?”

You can’t give anything to the Creator that does not already belong to him, thus he has no obligation to give anything back to you. But when he does, it is a condescension, and God’s condescension takes the form of covenants.

Nehemiah Coxe expressed this well.

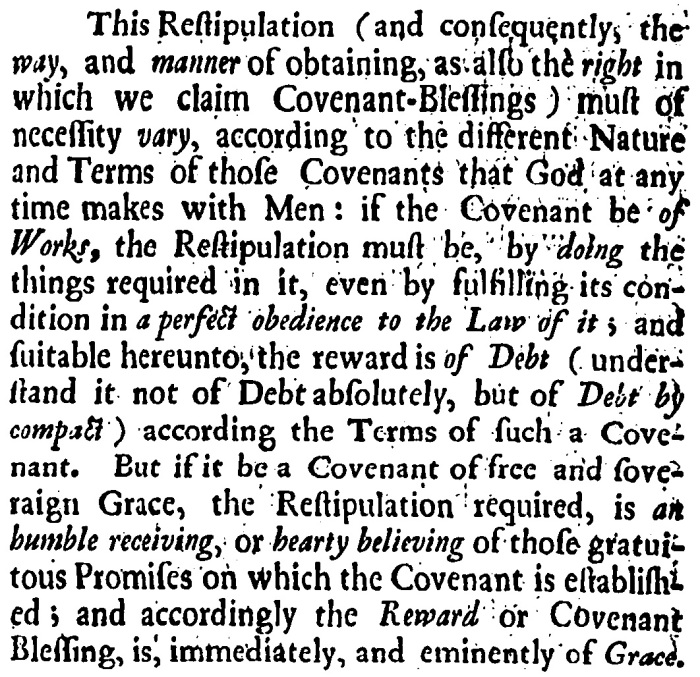

Later Coxe discusses man’s restipulation of the covenant. Restipulation refers to man’s response to God’s introduction/imposition of the covenant. If God places man under a covenant of works, man must work. If God places man under a covenant of grace, man must receive and/or believe the promises given to him.

Now, it would be easy to overlook but Coxe makes a brief mention of covenantal merit with respect to a covenant of works. He stated parenthetically that in a covenant of works when man fulfills the obligation he can expect the reward by debt, but this is a debt of compact, not absolute debt. Debt considered absolutely (i.e., on its own), would be something that automatically or intrinsically deserves or demands something. Coxe is saying that our works are not like that. They are not meritorious in and of themselves. But by way of compact, that is, according to some set of terms, a given obligation becomes worthy of a given reward. This is covenantal merit. God says, “Do this and receive that,” and there it is. Apart from God’s sovereign initiative and condescension, the work would earn nothing (even though it is demanded of us all the same).

Coxe goes on, explaining this further.

What are some of the takeaways from this?

1. The confessions confess the concept and principle of covenantal merit. God is so beyond man, the Creator so beyond the creature, that nothing could ever be performed by the creature in such a way that it would obligate the Creator to reward him. However, God has condescended to man by way of covenant, and has made promises to him.

2. Narrowing our focus to the London Confession, the confession confesses that God promised the reward of life to man through covenant. There was no other way man could have earned it. In other words, chapter seven confesses the covenant of works. Trace the reward of life in chapters 6, 19, and 20 and you will find this assertion further substantiated.

See also:

https://pettyfrance.wordpress.com/2013/09/19/covenantal-merit-definite-atonement-and-republication/

For those interested, here are some statements from John Ball that are pertinent to the language seen in the Westminster Confession

This one is quite significant, especially in light of the text used as proof.