On the Need for and Practice of Confessing the Faith

“Unity without verity is rather a conspiracy.” [1]

Truth is as unchanging as the Author of truth. It is the duty of the church to know, believe, and proclaim this truth. The theological vanguards of our day need not take us on a new path, but on the tried, tested, and true paths of the church throughout the ages. They may remove stones in the way, new or old. They may add clarity to the road we trod with clearer light. But they must keep us on that road. This can only be accomplished with a clear, comprehensive, and concise confession of faith.

The Need for a Confession of Faith

Communion is always built upon union. A confession of faith is thus necessary for the unity of individual churches and for the unity of multiple churches. It is the source of outward union upon which communion can take place. Nehemiah Coxe, a Particular Baptist, said,

There can be no Gospel Peace without truth, nor Communion of Saints, without an agreement in fundamental principles of the Christian Religion. We must contend earnestly for the Faith once delivered to the Saints; and mark those that cause divisions among us by their new Doctrines contrary thereto, and avoid them. [2]

Coxe was right. The foundation of unity must be truth, extrinsic to ourselves and objectively rooted in the God who is light, and in whom there is no darkness (1 John 1:5). A local church’s unity must be grounded on truth, and so also the unity of an association or denomination of churches must be grounded on truth. Communion derives from union.

The author to the Hebrews, after spending a great deal of time correcting errors and asserting truths, exhorted the recipients of his letter, “23 Let us hold fast the confession of our hope without wavering, for he who promised is faithful” (Heb 10:23 ESV). Their unity was to be founded on a collective and united confession of that which was true. And those who contradicted it were to be corrected or rejected. The church, locally and collectively, must confess the faith.

A confession of faith is necessary. There can be no meaningful unity without doctrinal agreement and commitment, and Scripture itself commands us to hold fast and guard the body of truths contained in the Scriptures.

The Practice of Confessing the Faith

This leads to how one confesses the faith. It is a sad day when what we confess and how we confess must be dealt with independently. A PCA minister and seminary professor once said, “There is no subscriptional method that will guarantee the orthodoxy of the next generation.” And he was right.

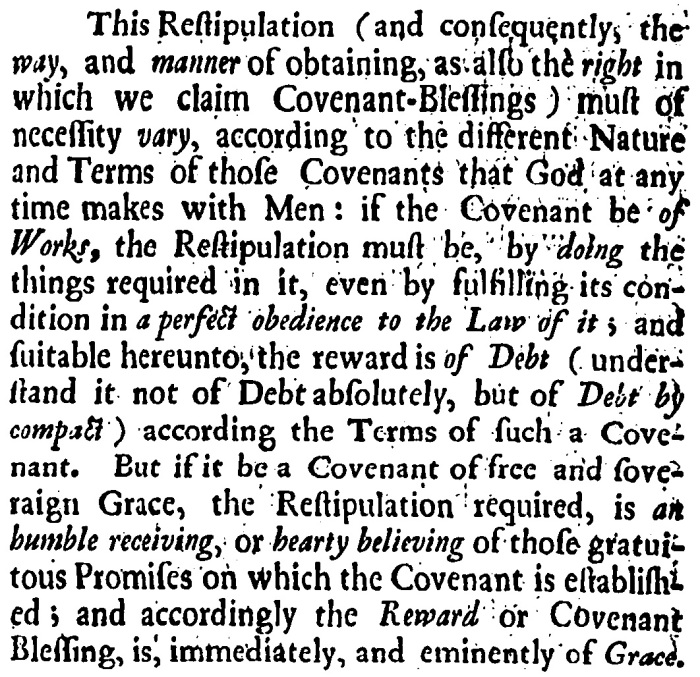

While subscriptional standards are a matter of wisdom, and worthy of discussion, there is a more fundamental issue that must be addressed. A confession of faith can be dealt with actively or passively. Actively, one confesses the faith, i.e. one confesses before God, brethren, and the world, that certain things are true. Passively, one uses a confession of faith as a reference document, more like a set of guidelines. In this second case, there is not an expectation that one necessarily confesses these things to be true, because one is not confessing the faith.

But to use a confession of faith in the second sense is directly contrary to the nature and function of confessions of faith because, as was just stated, it’s not confessing the faith. Indeed, if a confession is to be used as a set of doctrinal guidelines, then the word “confession” ought to be removed and replaced with “reference document,” “list of suggestions,” or “generalization of approximated truth.” Why hold to a confession of faith if you’re not confessing it to be true? Either remake the document or compose your own. And then confess that document. “Let your yes be yes, and your no be no” (Matthew 5:37, James 5:12).

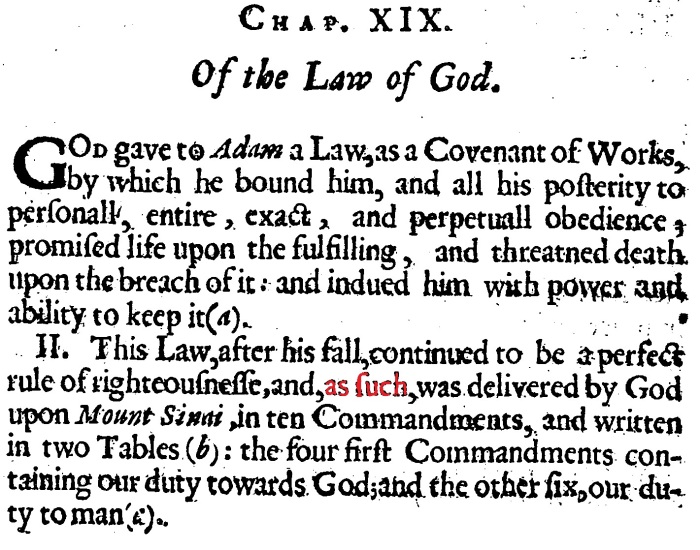

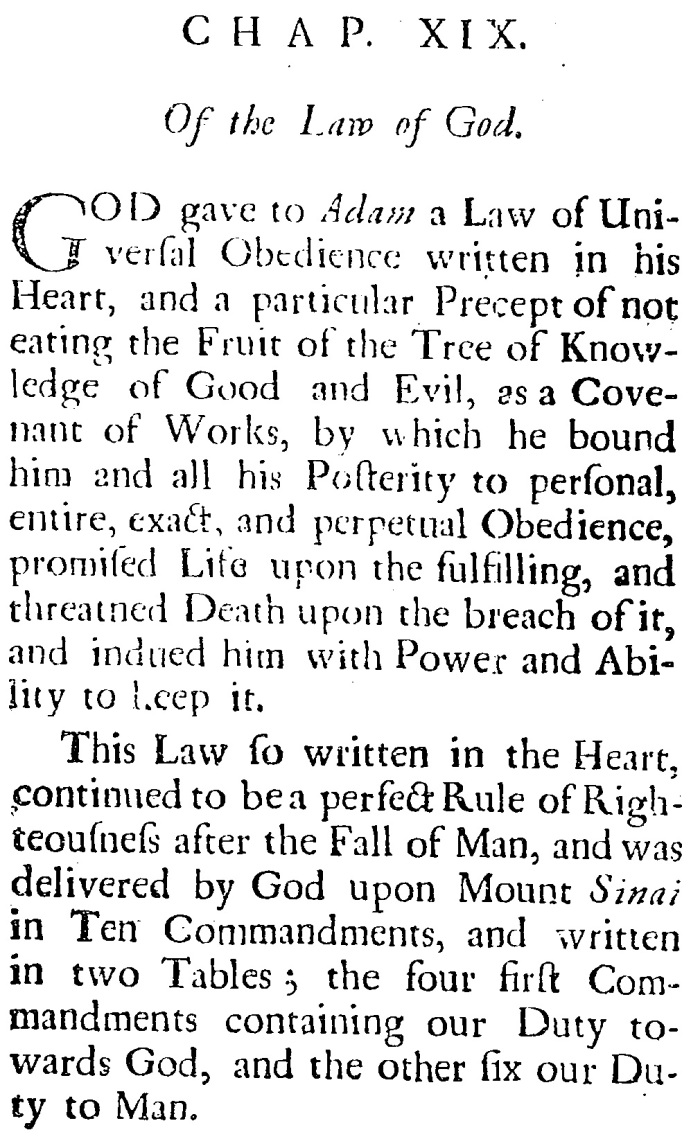

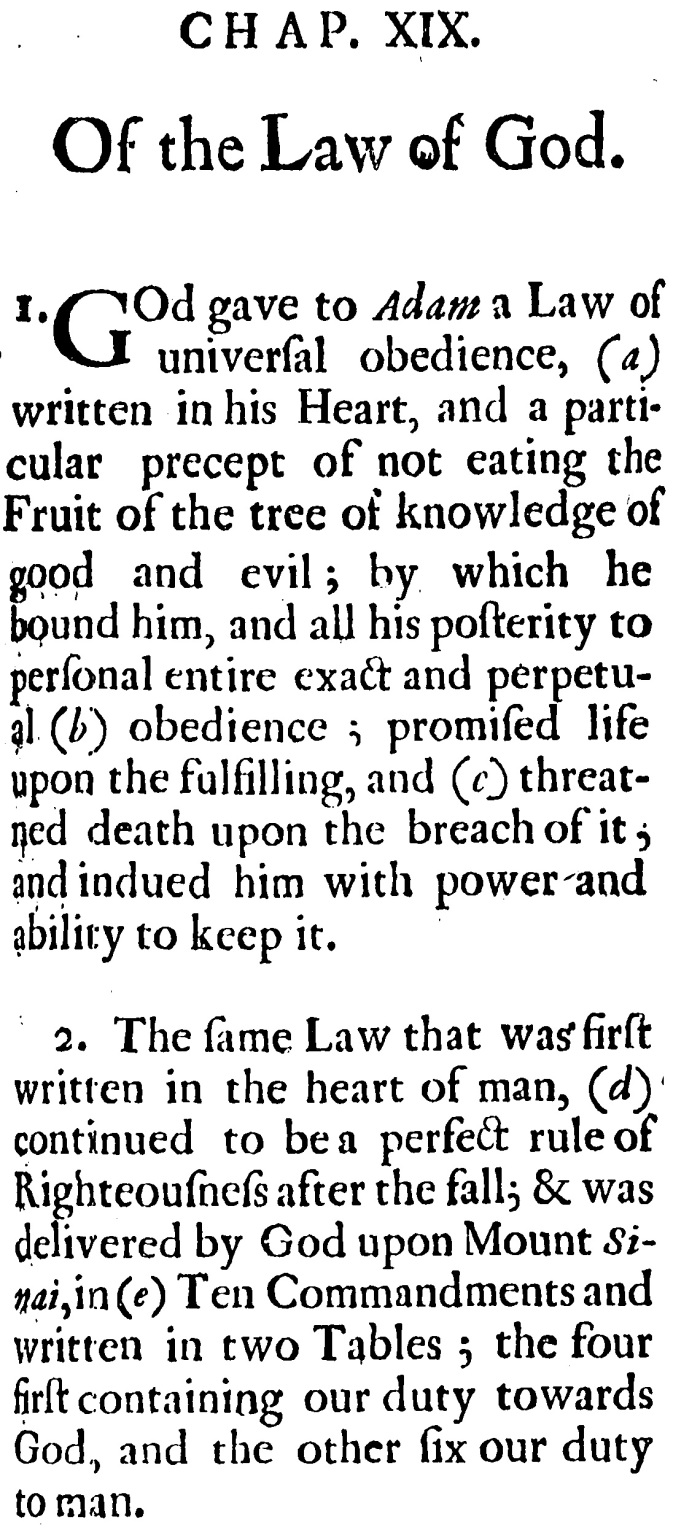

Returning to active confession, this is what confessions are all about. In the 1640’s and 1670’s, when the two major confessions of the Particular Baptists were first published, they wanted the country of England, and especially the civil magistrates, to know what it was they held to be true. Whether or not they were thrown in jail, fined, or persecuted depended on how the magistrate responded to such documents, if at all. The Particular Baptists wanted to vindicate their names from accusations of heresy and political suspicions. [3] They also desired to demonstrate their agreement with broader orthodox confessional Christianity. For this reason, and others, the editors of the confession made their intentions clear in the preface to the 1677 confession.

We did conclude it necessary to expresse ourselves the more fully, and distinctly…to manifest our consent with both (the Presbyterian Westminster Confession and the Independents’ Savoy Declaration), in all the fundamental articles of the Christian Religion. [4]

They said later, “We have exprest ourselves with all candor and plainness that none might entertain jealousie of ought secretly lodged in our breasts, that we would not the world should be acquainted with.” [5] They had nothing to hide. Their confession represented what they confessed to be true from the Scriptures.

This common sense approach to a confession played out during the hymn-singing controversy of the 1690’s when the Particular Baptists of the 1640’s were accused of believing that congregations were not obligated to remunerate their ministers. William Kiffin, a living member of that generation, replied by showing that the first confession of faith (1644, 1646) clearly stated that congregations should pay their ministers. He said “They must needs be the grossest sort of Hypocrites, in professing the contrary by their Profession of Faith, and yet believing and practising quite otherwise to what they solemnly professed as their Faith in that matter.” [6] Kiffin’s argument is that if the accusation is sustained (that the first Particular Baptists did not believe congregations should remunerate their ministers), then the confession contains a blatant lie, which was of course absurd. In a truly similar fashion, it is nothing short of falsehood to confess something to be true in a way that contradicts the thing which is being confessed to be true. Say what you mean, and mean what you say.

But this can become difficult even when committing two people to the same document. Indeed, it can become even more difficult when this document is a piece of times gone by. Yet the need for unity on a foundation of truth does not change, thus the need to confess the faith does not change. And when confessing the faith, the need to confess the faith honestly, sincerely, and openly does not change. If the faith you confess conceals or confuses, it’s not worth confessing.

The tried and true faith of the church of Jesus Christ is worth confessing. Hence, historical confessions of faith are worth confessing. And though they may require a certain amount of teaching and context in order to grasp their richness and true value, they are not mysteries designed to conceal. They are confessions designed to instruct and reveal.

When a group of persons or churches covenants to unite on a foundation of doctrinal unity, they are confessing one faith. If they are not, there is no point or purpose in the doctrinal commitments upon which they united. Those commitments aren’t representative of the group, and are thus misrepresentative.

Samuel Rutherford provides some helpful material for understanding the need for unity within a confession of faith. In one place, he argued against the objection that confessions of faith should be framed only in Scripture language by the fact that the Apostles argued via deductions and necessary consequences to vindicate themselves from charges of heresy that came from Jewish leaders. We must do the same, he argued. We must give an answer for the hope that lies within us in words that explain our meaning clearly. [7]

Likewise he argued that if all we use is Scripture language then not only would Jews falsely subscribe to our assertions about the Old Testament, but heretics likewise would do the same throughout. [8] A confession of faith thus represents the teaching of scripture, and explains it. Therefore, a confession is written with precision specifically to avoid contradictory meanings arising from one doctrinal assertion. [9]

As an example, Rutherford considered a suggestion for a confession of faith that would accommodate the views of Lutheran theologians. While not excommunicating the Lutherans theologically, Rutherford did not consider a common confession between them to be appropriate. Speaking of one particular meeting where views on the presence of Christ in the supper were discussed by both parties, he said,

But the truth is, there were contrary faiths touching the presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Sacrament; and therefore I humbly conceive all such General confessions as must be a coat to cover two contrary faiths, is but a daubing of the matter with untempered mortar…I speak not this as if each side could exactly know every lith [10] and vein of the controversy, for we prophesy but in part, but to shew I cannot but abominate truth and falsehood, preached up in one confession of faith.[11]

Rutherford is saying that while we cannot expect absolute unanimity, neither can we accommodate known contradiction. If two people agree to confess something to be true, they cannot and should not understand that truth in contradictory ways.

Rutherford provides an example of why this is so important and fundamental. He says,

For if two men should agree in such a bargain, A covenants with B to give him a ship full of spices; B promises to give a hundred thousand pounds for these spices, A believes they are metaphorical spices he gives, B believes they are the most real and excellent spices of Egypt; B promises to give a hundred thousand pounds of field stones, A expects good, real, and true money; this were but mutual juggling of one with another. [12]

When confessing the faith, there can only be true unity when that confession is confessed by the parties involved sincerely and truly without contradiction. Anything less is a farce, a “mutual juggling of one with another.”

Now, living in a fallen world hundreds of years since the publication of many of the documents that churches consider to reflect Scripture accurately, there has to be room given for learning and exploring the rich depths of such a confession. There is also some room given either for differing views which are intentionally accommodated by general language, or for exceptions to language that do not subvert the doctrine wherein they are taken.

Regarding general language, the Second London Baptist Confession (1677) intentionally accommodates varying views of the relationship between baptism and church membership (i.e., communion):

We have purposely omitted the mention of things of that nature, that we might concur, in giving this evidence of our agreement, both among ourselves, and with other good Christians, in those important articles of the Christian Religion, mainly insisted on by us. [13]

Rather than exclude their brethren of another opinion on this point, the Baptists avoided the topic. In other words, both groups could confess these truths sincerely because neither was forced to confess something that would contradict their own practice on this matter. This was done in order to “concur” and give “evidence of our agreement.” In this way, confessions are documents of unity, but not uniformity. A confession of faith commits a person to everything it says, but it may use general (nb: not contradictory) language in an intentional manner in order to accommodate diversity.

Regarding exceptions to a confession of faith, though they should be dealt with on a case by case basis, expressing one’s exceptions is of great importance for several reasons. First, it maintains active confession in the sense that one is clearly expressing potential disagreement rather than insincerely or falsely confessing something to be true. Second, it provides opportunities for further teaching, correction, and refining of one’s own views when the collective knowledge and insights of a church/association/denomination can be channeled into one’s own evaluation of such issues. Third, it may bring to the surface substantial and indeed unacceptable deviations from what a church/association/denomination confesses to be true. All of this preserves the doctrinal integrity and unity of the church/association. What has been described assumes, of course, that the men of the church/association/denomination know what they are confessing, and thus know where and why they take exceptions, if they take exceptions.

But what ought to be done when an exception arises that not only contradicts the teaching of the confession but also destroys it? The first thing that needs to be said is that we should pursue every possible avenue in order to restore unity through restoring doctrinal integrity. Nevertheless, if we actively confess the confession, allowing or accommodating a view that destroys what we confess to be true necessitates either a complete restructuring of what we confess to be true, or abandoning confessing the faith for referencing the faith (i.e., downgrading one’s subscriptional standard). But truth should not and must not be sacrificed for unity because truth is the foundation of unity.

If a serious doctrinal aberration arises, then let it be clearly stated. Let the one(s) owning it submit themselves to the accountability of their church/association/denomination, being wisely willing to yield and open to reason (James 3:17), let it be clear that if they persist in error they must leave or be removed, and let all involved sincerely confess the faith.

The Prerequisites of Robust Confessionalism

The church must confess the faith. It is necessary. The church must confess the faith. It is necessary. In order to accomplish this, one needs:

1. A good confession of faith

2. Christians who understand and confess the confession

3. Christians who will hold each other accountable to the confession

Apart from these pillars, robust confessionalism cannot take place. Being “confessional” is sometimes looked down upon. But if a confession of faith is a statement of what the Bible teaches then all it means to be “confessional” is that one is willing to stake their claim and plant their flag upon a doctrinal hill. Is that not what every Christian is called to do? Certainly it is.

And though there will be misunderstanding or lack of understanding of one’s confession (new or old), are we willing to be corrected? Are we willing to learn? Are we willing to grow in our commitments? Christians, churches, associations, and denominations experience growing pains. So also, we need to be those who, upon realizing we misunderstood something about our doctrinal commitments, are willing to be corrected or are willing to say that we cannot in good conscience uphold such a commitment. Both options are honorable.

It is dishonorable, however, to demand approval and acceptance in a way that contradicts the very commitments held by a church/association/denomination. Communion derives from union. Once you allow contradictory views of the same words within a confessional context, you have neutered all accountability and eroded the ability to work together formally or to present a united voice of truth to a watching world. You have asked all in communion to abandon the source of their union. To permit this reduces an objective body of doctrine to a subjective reference manual.

We submit ourselves not to any man, but to Scripture. Yet, we submit ourselves to a specific understanding, interpretation, and systematization of Scripture, i.e. a confession of faith. Consequently, we mutually hold one another accountable to that standard of truth. We cannot do otherwise. Our consciences are bound, so long as we hold these commitments. We are all responsible for holding fast the confession of our hope, standing firm and faithful at our posts and doing our part to keep the ship afloat and running smoothly, knowing and trusting that Jesus Christ is active and present in and among his churches in and by his Holy Spirit.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we may not be able to guarantee the orthodoxy of the next generation, but we can do everything in our power, with God’s blessing, to leave an orthodox church for them to inherit. “22 A good man leaves an inheritance to his children’s children” (Pro 13:22 ESV). So then, whatever we confess, let us confess it together. After all, “There can be no Gospel Peace without truth, nor Communion of Saints, without an agreement in fundamental principles of the Christian Religion.” In so doing, as we face the attacks of our own hearts, the evil one, and the world, we will be able to stand side by side, holding fast the confession of our hope, saying to one another what Jonathan’s armor-bearer said to him, “Do all that is in your heart. Do as you wish. Behold, I am with you heart and soul” (1 Sam 14:7 ESV).

[1] Anon, A Brief History of Presbytery and Independency (London: Edward Faulkner, 1691), 30.

[2] Nehemiah Coxe, Vindiciae Veritatis, Or a Confutation of the Heresies and Gross Errors of Thomas Collier, (London: Nath. Ponder, 1677), 4 of an unmarked preface.

[3] Hence the recurring refrain marking their literature: “By those who are commonly, but falsely, called Anabaptists.”

[4] Anon., A Confession of Faith Put Forth by the Elders and Brethren of Many Congregations (London, 1677), 3-4 of an unmarked preface.

[5] Anon., A Confession of Faith, 5 of an unmarked preface.

[6] George Barret, William Kiffin, Edward Man, Robert Steed, A Serious Answer to a Late Book, Stiled, A Reply to Mr. Robert Steed’s Epistle Concerning Singing (1692), 18.

[7] Samuel Rutherford, A Free Disputation Against Pretended Liberty of Conscience (London: Printed by R.I. for Andrew Crook, 1649), 29.

[8] Ibid., 31. This same point was made between Nehemiah Coxe and Thomas Collier. Coxe said that “Whereas Mr. Collier tells us, That he saith what the Scripture saith, &c. That is not enough, unless he make it manifest also, That he saith it according to the true sense and intendment of the Spirit of God in those Scriptures he refers unto.” He adds, “Those Socinians…have yet said as much as Mr. Collier here presents us with.” Coxe, Vindiciae Veritatis, 2. Collier did not appreciate this and replied that Coxe was claiming a pope-like authority and infallibility to make such a demand from Collier. Cf. Thomas Collier, A Sober and Moderate Answer to Nehemiah Coxe’s Invective (Pretended) Refutation (as he saith) of the gross Errors and Heresies Asserted by Thomas Collier (London: Francis Smith, 1677), 1-2.

[9] We should note that the precision of the orthodox confessions of faith is oft overlooked or invisible to modern Christians because we live in a world (particularly in secular and religious education) predominantly devoid of the methods, premises, and arguments that led to the summarized conclusions of the confessions. The confessions are carefully handcrafted masterpieces of theological truth and collective Christian wisdom. We ignore the precision of their thought and language to our own peril.

[10] A limb or branch.

[11] Rutherford, A Free Disputation, 67. Spelling updated.

[12] Ibid. Spelling updated for ease of reading.

[13] Anon., A Confession of Faith, 139. Spelling updated.