In this post, I want to focus on Dr. R. Scott Clark’s use of the phrase “in, with, and under” in his recent post about differences between the Reformed view of OT saints’ experience of the benefits of Christ through typology and the Particular Baptists’ views of the same. It appears in the title and throughout the post itself and is used to describe the Reformed position, positively, and the Particular Baptist position, negatively:

…in the Reformed view (see below) the Christ and his benefits, the substance of the covenant of grace, are in, with, and under the types and shadows. For the PBs [Particular Baptists] Christ and the covenant of grace cannot be in, with, and under the types…

Is this language helpful for discussing either the views involved, or the theology itself? I contend that it is not. Why?

“In, with, and under” is not Helpful

First, the phrase itself “in, with, and under” has quite a history, as of course Dr. Clark knows well. The phrase is unavoidably attached to the Lutheran view of the presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper, teaching that by virtue of the union of Christ’s humanity to his deity, his glorified body is ubiquitous, and therefore is “in, with, and under” the elements of the Lord’s Supper (albeit illocally).

Rightly or wrongly, the Reformed regarded this view as “consubstantiation” because the substance of the glorified body of Christ is “in, with, and under” the substance of the bread and wine. This makes Christ’s body “consubstantial” with the elements.

Richard Muller argues that “consubstantiation” is not an accurate representation of the Lutheran view. Nevertheless, as demonstrated at the end of this post in quotations from William Ames, David Dickson, and Edward Polhill, the Reformed rejected the language of “in, with, and under” as used by the Lutherans, and often called such language “consubstantiation.” The Reformed denied any bodily presence in the Supper and instead taught that Christ is really present, spiritually, to the faith of believers.

Whether the Reformed were accurate in their depictions of the Lutheran view, it is not helpful to use a well-known formula with a history relating to a doctrine specifically rejected by the Reformed as the explanation for a Reformed doctrine.

Second, I am glad to be corrected here, but I am not aware of the phrase “in, with, and under” having a place in the Reformed tradition’s explanations of the relation of Christ to OT types. It is unsurprising to me that the phrase would not have a history in the Reformed tradition, given the previous point. So then, why use language to describe the Reformed that they themselves did not use?

It is not helpful to use a phrase without a history within the Reformed tradition as the descriptor for Reformed theology on that point.

Third, appealing to metaphysical categories to affirm things about signs is notoriously problematic. It was precisely this that made debates about transubstantiation and consubstantiation so bewildering to navigate. As shown in the quotes at the end of this post, the Reformed response to consubstantiation was that it was essentially nonsensical. Polhill calls the Lutherans explanations of consubstantiation “strange Riddles [which they] must maintain to make good their opinion.”

I have high confidence that Dr. Clark does not read “The Rock was Christ” as a metaphysical statement just as he does not read “This is my body” as a metaphysical statement. So, why use metaphysical language here? What does it mean for Christ to be “in, with, and under” animal sacrifices or a bronze serpent or any of the other types of the OT? What does it affirm? It sounds to me more like “strange riddles” than clear teaching. It is not helpful. The language is more difficult to explain than the concepts.

To be abundantly clear, I am not suggesting in any sense that Dr. Clark is adopting or promoting the Lutheran position on the Lord’s Supper. I am questioning the wisdom of Dr. Clark’s use of the language of the Lutheran doctrine of consubstantation for a discussion of typology.

Signs and Things Signified (Again)

I would suggest that the more common Reformed terminology of signs and things signified is superior, and better equips us to speak about the issue. WCF 27.5 will suffice to demonstrate the point.

The Sacraments of the Old Testament, in regard of the spiritual things thereby signified, and exhibited, were, for substance, the same with those of the New. (WCF 27.5)

Note the designation of “the spiritual things thereby signified” as the substantial continuity between the OT and NT signs. David Dickson, in his comments on the Westminster Confession explains that this substantial continuity is not located in the signs themselves, but the thing signified:

which is not done by reason of the sign, for the signs are diverse and different: therefore it must be done, by reason of the thing signified

A discussion of signs and things signified is far more fruitful and productive than a discussion of Christ being “in, with, and under” OT signs. Why is that?

It is far more helpful because it is a context in which I can clearly state my own position, namely, that Scripture teaches that OT signs signify two things. The first thing signified is something in the original context of the sign. The second thing signified is indeed “for substance, the same with that of the New.” I have recently explained this here.

It would be very easy for Dr. Clark to affirm or deny arguments in such a discussion.

Missing the Mark

In light of this analysis, what are we to make of Dr. Clark’s words, provided above:

…in the Reformed view (see below) the Christ and his benefits, the substance of the covenant of grace, are in, with, and under the types and shadows. For the PBs [Particular Baptists] Christ and the covenant of grace cannot be in, with, and under the types…

Dr. Clark’s descriptions of Particular Baptists just don’t fit. (Richard Barcellos is publishing brief articles detailing more on this. The first is available here.) There is an agreement between the Reformed and the Particular Baptists that the “spiritual things thereby signified” are one and the same from OT to NT.

Built on this, Dr. Clark’s repeated insistence that the Particular Baptists and the Reformed are so very different, based on the language of Christ being “in, with, and under” types, misses the mark. Likewise, the recent flurry of posts quoting Reformed theologians asserting the substantial unity of OT and NT administrations misses the mark (assuming that Dr. Clark intends them to be aimed at Particular Baptists). Those criticisms or arguments simply don’t land on the Particular Baptists. (See more on the language of “administration” here.)

The question is not whether “the spiritual things thereby signified” are one in substance between the OT and the NT. That is where we are agreed. The question is whether there is an original context for types that is, in fact, in itself, distinct from their antitypes. In other words, the question is whether types signify two things.

In light of the arguments presented in this post, I simply refuse to accept the language of “in, with, and under” as the terms of this debate or an accurate descriptor either of Reformed theology positively or Particular Baptist theology negatively. By doing so, I am by no means rejecting the use of historial categories and terms related to this subject. To the contrary, I am insisting that we stick to historical categories of signs and things signified.

And all I would like to know is, did the OT types signify one thing or two things?

Sources on the Reformed rejection of Consubstantiation and the language of “in, with, and under.”

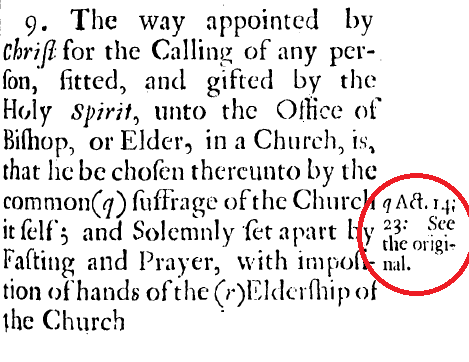

William Ames, The Substance of Christian Religion (London: Thomas Mabb, 1659), 184-185.

For this spiritual nourishment in the Supper it is not required, that the bread and wine be substantially changed into the body and blood of Christ; nor that Christ be bodily present, in, with, and under the bread and wine; but onley that they be changed as to relation, and application or use; and that Christ be spiritually present onely to such as partake in faith.

This is hence gathered, in that bread and wine are said to remain here in the Supper; and our communion with Christ, is in a sort said to be such, as Idolaters have with their Idols; which stands in relation onely. Therefore, Transubstantiation of Papists and Consubstantiation of Lutherans fight:

Reas. 1 [fight] With the nature of Sacraments in general, whose nature consist in a relative union, or likeness, as hath been explained; not in a bodily succession of the one, in the others place, or a substantial change of the one into the other; nor yet in a bodily conjunction or presence of the one with, in, and under the other.

David Dickson, Truth’s Victory Over Error (Edingburgh: John Reed, 1684), 298-301.

Quest. V.

Is the Body and Blood of Christ in this Sacrament corporally, or carnally in, with, or under the bread and wine?

No. 1 Cor. 10. 16.

Well then, do not the Lutherians err, who maintain, that the body and blood of Christ, are corporally in, with, and under the bread and wine: and that (as the Papists also teach) his body and blood, are taken corporally by the mouth, by all Communicants, believers, and unbelievers?

Yes.

By what reasons are they confuted?

(1) Because, Christ was sitting with his body at the Table. (2) Because, he himself did eat of the bread, and drink of the wine. (3) Because, he took bread from the Table: he took not his own body: he break bread, and did distribute it, he break not his own body: so he took the Cup, and not his own blood. (4) Because, Christ said, the Cup was the New Testament in his blood: but the Cup is not in, with, and under the Wine. (5) Because Christ said, the bread was his body, which was broken; the Wine was his blood, which was shed. But neither was his body broken under the bread, nor his blood shed under the Wine, seeing Christ as yet, was not betrayed, crucified, and dead.

In the next place, the end of the Lords Supper is, that we may remember Christ, and declare his death until be come; Luke 22. 19. 1 Cor. 11. 24, 25, 26. Therefore if Christ be now present with his body, in, with, and under the bread, the Sacramental remembrance of Christ, and the declaring of his death, ought to cease.

This Doctrine of Consubstantiation, is contrary to the Articles of our Faith. It is against the Truth and Verity of his Humane Nature, which is visible, palpable, and in a certain place circumscriptive. It is against the Article of his ascension: for it makes his body, which is now in Heaven, until the last day, to be in, with, and under a piece of bread. It is against the spiritual communion of the Saints with Christ the Head, which the Lutherans makes by this doctrine a corporal and carnal communion, contrary to 1 Cor. 10. 3, 4. Ephes. 1. 22. Ephes. 4. 4. Rom. 8. 9. 1 Cor. 6. 17. 1 Iohn 4. 13. Iohn 15. 5.

It brings with it many and great absurdities; as that the body of Christ, Non habeat partem extra partem; hath not one part of it without another; but as if all the parts of his Body, were in one part, which is contrary to the Nature of a true and real Quantum, which consists essentially in three dimensions, length, breadth, and thickness. It makes in effect his Body to be no body. It brings down the glorious Body of Christ from Heaven, and puts it under the base Elements of this Earth. It makes as many bodies of Christ, as there are pieces of Eucharistical bread. It makes his body to be broken in, with, and under the bread, and bruised with the teeth: It sends his Body down to the stomach, where it is turned into a mans substance, and afterwards throwen out.

Moreover, all true Eating brings life and Salvation; Iohn 6. 50, 51. but eating by the mouth profiteth nothing; Iohn 6. 63. Again, our union with Christ, (and therefore our eating of his Body, from whence ariseth this union) is not corporal but spiritual; Eph. 3. 17. And the Body and Blood of Christ, are meat and drink; not carnal but spiritual; even as the hunger, whereby we long for this meat is spiritual: and the life to which we are nourished, is spiritual, and the nutriment is spiritual. Lastly, according to this Doctrine of Consubstantiation, stiffly maintained by the Lutherians, it follows, that Christ did his own body, while he did eat the bread of the first supper. That his Disciples did eat their Lord and Masters Body. That Christ before he was crucified, was dead: That his Disciples were more cruel and inhumane to him than the Iews were that crucified him: That he is often buried within the intrals of wicked men.

Edward Polhill, Christus in Corde: Or, The Mystical Union Between Christ and Believers Considered (London: A.M., 1680), 219-220.

As touching the Will of Christ, expressed in those words, This is my body. The Lutherans seem to stand for the letter of the Text; but their Interpretation is not a litteral one, “This” is not properly “in, with, and under this” in propriety. “This is my body” is one thing, “in, with, and under, This is my body” is another; neither is their Interpretation true. Baptism is a Sacrament of the New Testament as well as the Lords Supper; as in the one, the blood of Christ is not in, with, and under the water; so in the other, the body is not in, with and under the bread; the reason is alike in both Sacraments. If in the Eucharist the body be in, with, and under the bread, then the blood is in, with, and under the wine; consequently the blood is separate from the body. There is put upon Christ now in Glory, not to say, a second passion, but as many passions as there are Eucharists. It is not easie to imagine how the bread should be broken, and the body under it, not be so; or how the body should be broken on Earth, and at the same time glorious in Heaven; or how the same body as the same instant can be present in as many distant places as there are Eucharists in the world; or, if such a Presence might be, how the body could be finite, or indeed a body. All which strange Riddles the Lutherans must maintain to make good their opinion.